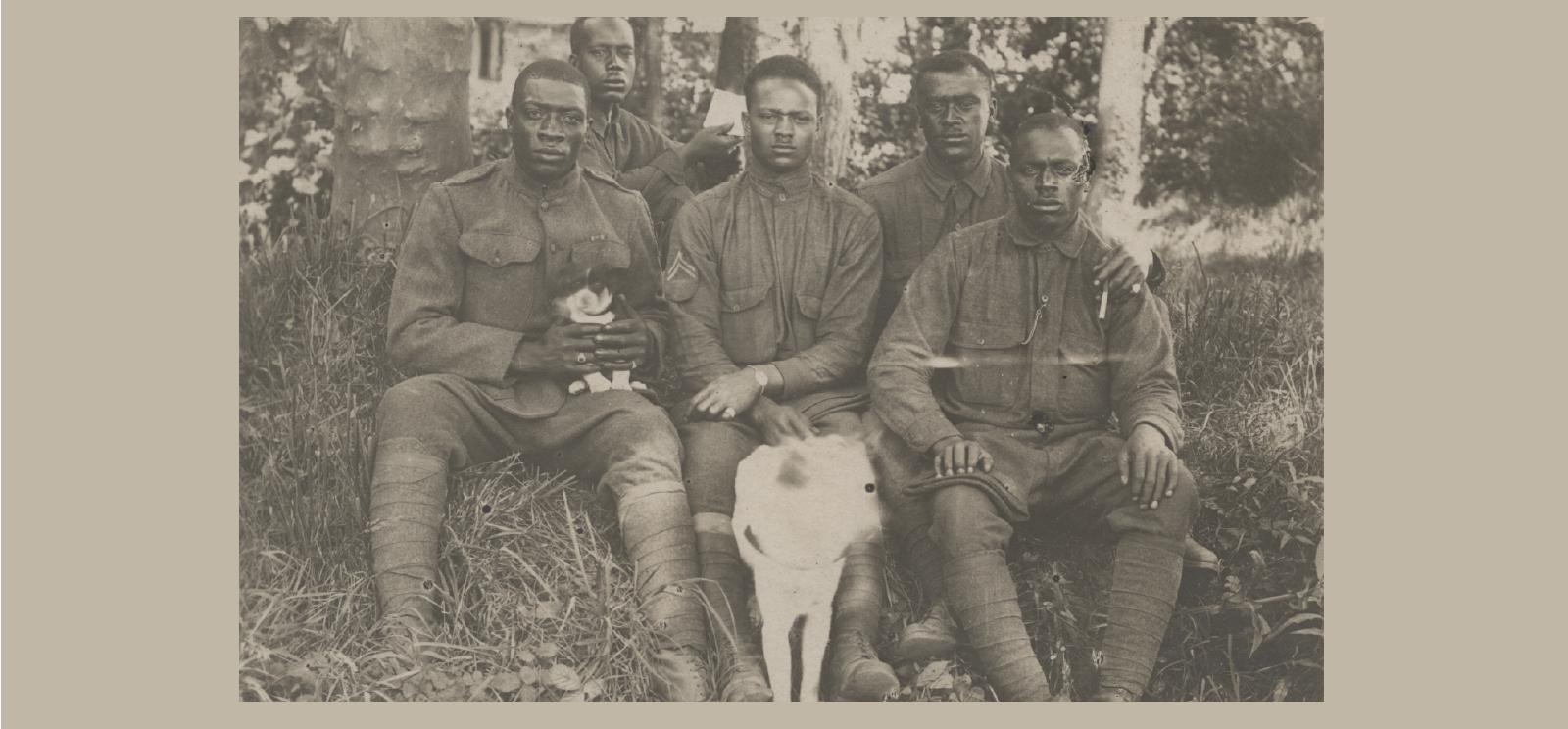

African American soldiers in uniform seated casually in wooded area with two dogs. Object ID: 1980.105.6

African American History and WWI Index

Background

By 1900, the U.S. government had abolished slavery, granted citizenship to African Americans and ratified the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments establishing their right to vote. Yet Americans throughout the country continued to overtly discriminate against Black Americans.

An organized national movement advocating for Black American civil rights emerged in response, chiefly represented by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Leaders and civil rights activists such as Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois fought the political and social backlash against increased liberties for Black Americans – including the Wilson Administration segregating the entire federal government in 1913.

Great Migration and War Support

Though the United States did not join World War I when it began in 1914, Black Americans found new opportunities created by the conflict. With Europe at war, fewer European immigrants came to the U.S., fueling a labor shortage as industries increased war production. Demand for workers created openings for many Black Americans to escape rural poverty, Jim Crow laws and violence at the hands of white supremacists in the South.

They sought increased economic and civil opportunities in new cities, previously inaccessible to them in the South. Discrimination, segregation and violence still existed in the North, but the prevalence and frequency were reduced.

By the summer of 1919, approximately 500,000 African Americans had resettled in the North. This first phase of the Great Migration would continue up to the Great Depression in the 1930s.

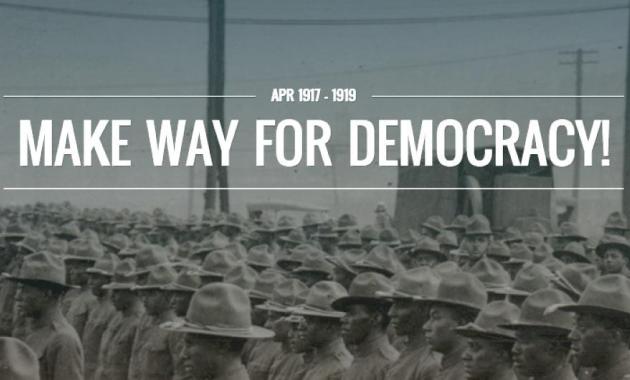

On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany. In his statement, he demanded that “the world must be made safe for democracy. Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty.” But democracy was not safe in the United States – African Americans did not have full political liberties throughout the nation, with Wilson himself being a key player in walking back equal access during his time in office.

“Let us, while this war lasts, forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our own white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy.”

—W. E. B. DuBois, The Crisis, July 1918

After the U.S. entered the war, people recognized that all workers regardless of color were important to the patriotic effort. Many African American men volunteered for service in the armed forces or with organizations such as the YMCA (Young Men’s Christian Association).

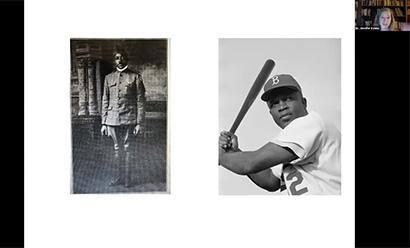

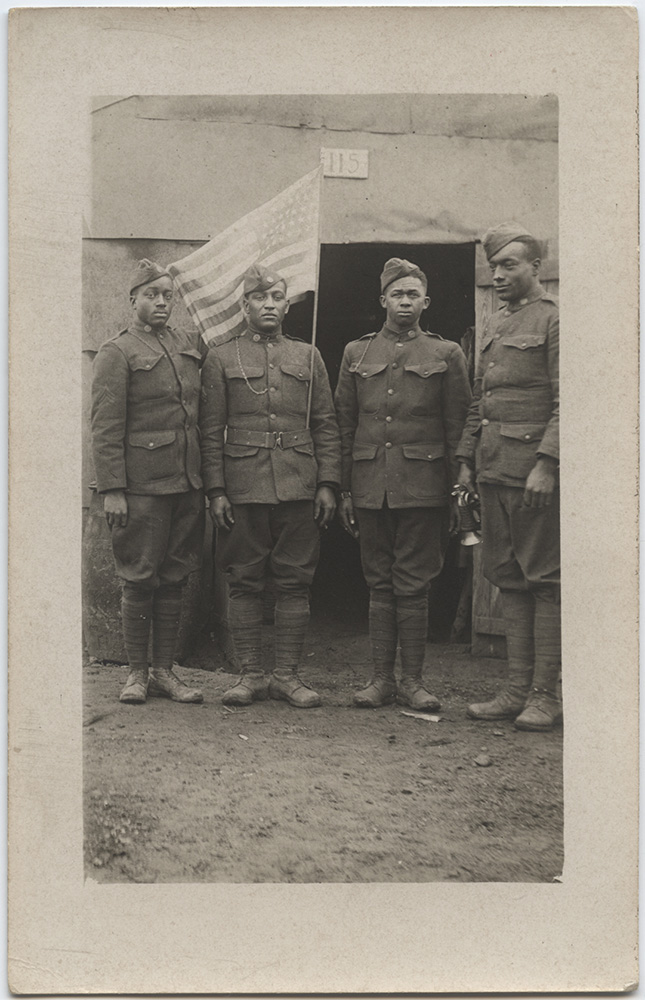

Black American Military Service in WWI

When the United States entered WWI, several thousand Black Americans were serving in the National Guard and 10,000 Black soldiers served in four segregated units within the regular U.S. Army. These units – the 24th and 25th Infantry and 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments – were the famous “Buffalo Soldiers” who gained their moniker and fame on the Western Frontier during the American Indian Wars in the late 1800s. These units, however, were not sent to fight in Europe. Instead, they provided non-commissioned officers and specialists for the new African American units created from volunteer and drafted troops.

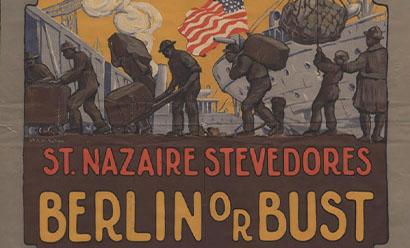

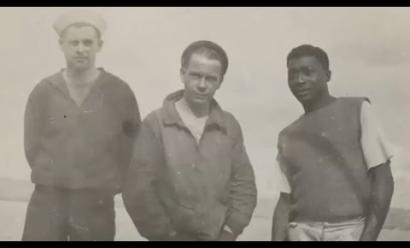

As Black doughboys and sailors fought to “make the world safe for democracy,” they also faced a two-front battle for equality within the military as well as back home. Many government officials and military commanders baselessly doubted that African American troops could perform well in combat. They assigned approximately 89% of Black servicemen (compared to 56% of all other soldiers) into supply, construction and other labor or support units – and often ordered these units to perform the most tedious, arduous and at times gruesome tasks.

White military commanders denied seasoned Black servicemembers (many of them decorated) opportunities for leadership in WWI.

Despite white American officers’ prejudices, two African American combat divisions were formed and saw combat on the Western Front in Europe:

- The 92nd Division, under U.S. command.

- The 93rd Division (comprised of four Infantry Regiments: the 369th, 370th, 371st and 372nd), initially under French command.

Even when under French command, many white American officers sought to maintain racial discrimination against Black troops. General John J. Pershing, the commander of the AEF, communicated to the French commanders that they were not to treat African American troops as equals.

Colonel Franklin A. Denison was the regimental commander of the 8th Illinois in that state’s National Guard. When it was federalized, it became the 370th US Infantry Regiment. Upon their departure for France, Colonel Denison was replaced by a white officer. Otis B. Duncan was the second in command, with the rank of Lt. Colonel, and remained in command of one of the regiment’s three battalions. Lt. Col. Duncan became the highest-ranking African American servicemember in the AEF.

Yet the 369th Infantry Regiment (part of the 93rd Division) established an excellent reputation fighting under the French, earning the nicknames “Harlem Hellfighters” and “Harlem Rattlers.” Sgt. Henry Johnson was the first American recipient of the French Croix de Guerre for bravery; Private Needham Roberts was the second.

A total of 68 Croix de Guerre and 24 Distinguished Service Crosses were awarded to men of the 93rd Division along with several unit commendations, making it one of the most decorated American units of the war.

By the end of hostilities in November 1918, 2.3 million Black men had registered for the draft and close to 370,000 saw service.

Black Women’s Service

African American women supported the war effort as nurses, ambulance drivers, Navy Yeomen, club administrators, office workers, railroad workers, munitions workers, relief organization volunteers and extremely successful fund-raisers for a variety of government organizations and causes.

Twenty-three Black women served abroad with the YMCA. They managed leave stations, canteens, and hostess houses (where soldiers socialized) for Black troops.

American Red Cross policies permitted Black women to be ambulance drivers, but did not allow them to apply as nurses until late 1918.

“They went into every kind of factory devoted to the production of war materials, from the most dangerous posts in munitions plants to the delicate sewing in aeroplane factories. Colored girls and colored women drove motor trucks, unloaded freight cars, dug ditches, packed boxes. The colored woman running the elevator or speeding a railroad on its way by signals was a common sight.”

—Alice Dunbar-Nelson, African American poet and civil rights advocate recognized for her mobilization of African American women for the Council of National Defense

We Return...

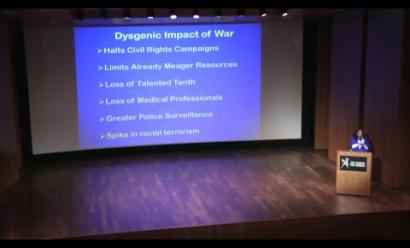

After the war, as millions of military personnel were discharged back to their homes and domestic lives, racial tensions across the United States intensified. Many Black leaders encouraged returning servicemen to fight for the dignity and respect earned during military service. W. E. B. Du Bois famously called upon Black veterans to not simply “return from fighting” but to “return fighting.”

The influx of returning men meant competition for shrinking economic opportunities in postwar America. New social movements toward equality and fair treatment inflamed white supremacists in the South and North, leading to the “Red Summer” of 1919. Racist violence broke out in at least 26 cities. White Americans met many Black veterans with hatred and mistreatment, and in some cases attacked them while they were in uniform – ultimately lynching 83 Black men (11 of them uniformed) in 1919.

“That’s one of the most beautiful sights to see the American flag unfurled and see those soldiers... it makes you proud that you are an American citizen. It makes you proud that you serve – notwithstanding the fact of all the injustices. Being denied the opportunities, being in a Jim Crow car, letting the German soldiers eat before we did – but still America is a great country. I felt even at that time, after the war was over, if the war was ever to happen again, I would go back and fight again.”

—Robert L. Sweeney, an African American soldier who served in the 92nd Division, AEF

Resource Hub

More Articles

Teaching Lessons

Videos/Lectures

WWI and African American Experiences

Find even more lectures in the “WWI and African American Experiences” playlist.

Exhibitions and Collections

Make Way for Democracy!

In an era of federal segregation, the national call as "champions of the rights of mankind" rang hollow. Many African Americans saw the war as an opportunity to redefine their U.S. citizenship and improve social, political and economic conditions. Make Way for Democracy! portrays the lives of African Americans during the war through a series of rare images, documents and objects.