American servicemen returned from the First World War only to find a new type of violent conflict waiting for them at home. An outbreak of racial violence known as the “Red Summer” occurred in 1919, an event that affected at least 26 cities across the United States.

Racial tensions across the U.S. were exacerbated by the discharge of millions of military personnel back to their homes and domestic lives following the end of the war. Competition for opportunities in postwar America combined with a radically changed social landscape placed Whites and Blacks in conflict with one another, leading to tragic results.

World War I intensified the Great Migration, the mass emigration of African Americans from the rural South to the industrial North and Midwest in hopes of escaping the poverty and discrimination of Jim Crow laws. By the summer of 1919, approximately 500,000 African Americans had resettled in northern cities. In many cases, northern Whites—many of them newly arrived immigrants themselves—did not welcome Black newcomers.

When the war ended many returning servicemen resented that their vacated jobs had been taken, particularly by African Americans. Black laborers already suffered from a negative reputation in the White working community for their use as low wage-earning strike breakers, or “scabs,” who would keep factories in operation while the employees went on strike. The situation was made worse in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1917. Many officials and others, with little or no evidence, suspected Black workers of being pawns of Bolsheviks and anarchists.

Many Whites feared that the return of tens of thousands of Black veterans, with experience living abroad and, more significantly, having received military training, would be unwilling to resubmit to traditional political and social subjugation in the U.S.

Many Black leaders encouraged returning servicemen to assert themselves and fight for the dignity and respect they had earned through their military service. W.E.B. Du Bois famously called upon Black veterans to not simply “return from fighting” but to “return fighting.” Many Black veterans were mistreated, and in some cases, attacked while in uniform. Lynchings increased from 64 in 1918 to 83 in 1919. Membership in the revived Ku Klux Klan, reborn after D.W. Griffith’s 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, skyrocketed into the millions by the early 1920s.

Most violent incidents during the Red Summer of 1919 were not initiated by fringe white supremacist terror groups. Ordinary white civilians and veterans, unaffiliated with the Ku Klux Klan or any other racist organization, formed most of the mobs. Many of the dozens of incidents that occurred over the course of the year were made far worse because local, state and federal officials hesitated in taking action or turned a blind eye to the violence. Racial violence broke out in some of the nation’s most populous cities.

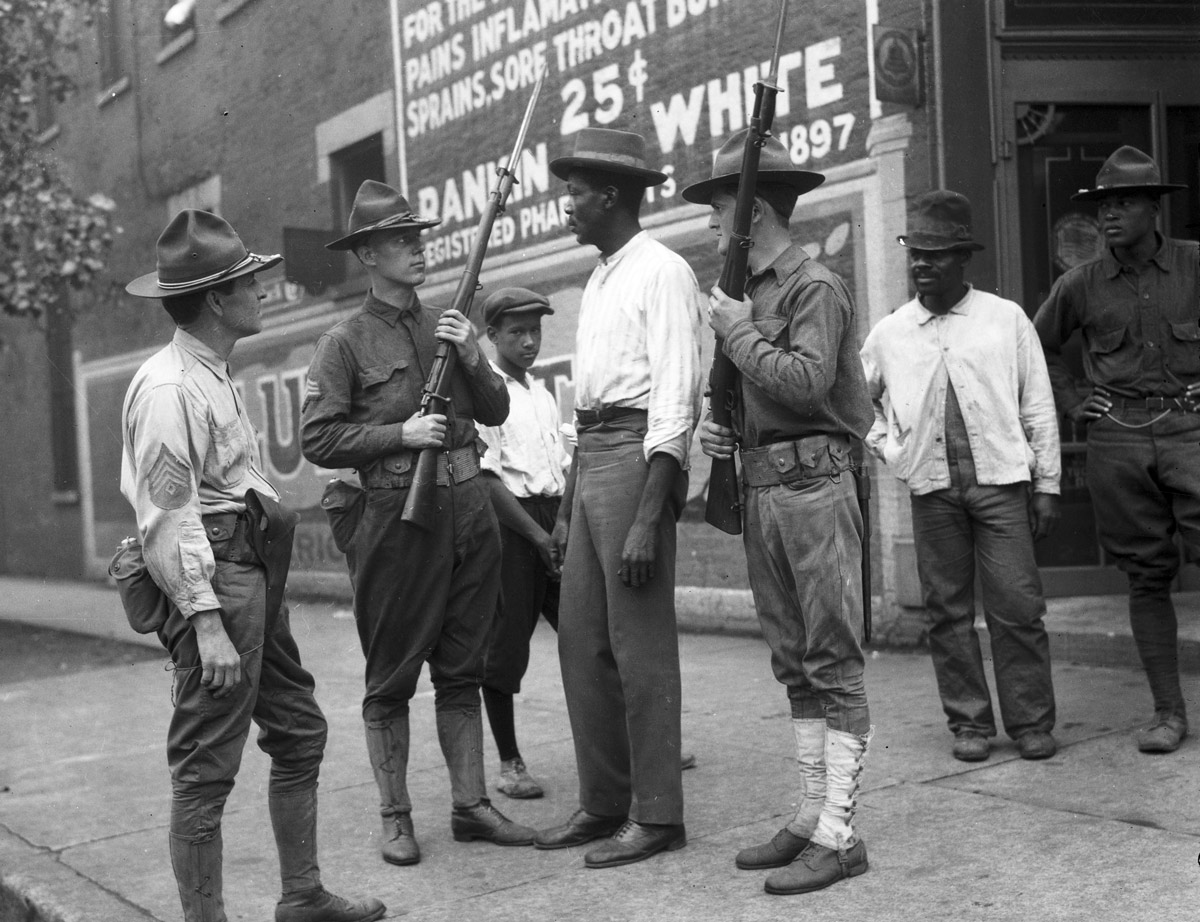

A four-day riot in Washington, D.C. began on July 19 when a rumor that Black men had assaulted a white woman incited mobs to attack local Black neighborhoods and assault random African American individuals on the streets. Off-duty sailors and recently discharged Army veterans led the mobs.

When the local police were overwhelmed by the mayhem, Washington’s Black community banded together to fight back, arming themselves with bats, clubs, pistols and knives. Soon, Black mobs were attacking white passersby just as indiscriminately as Whites did to Blacks. In nearby Norfolk, Va., a parade celebrating the return of a unit of African American troops from Europe turned into a bloody melee and two Black servicemen were killed. Ultimately, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson had to order troops to secure the streets.

Washington was closely followed by a massive race riot in Chicago. Rioting erupted on July 27 when a Black teenager drowned after being hit with stones when he and friends drifted near a de facto whites-only beach. Violent rioting across Chicago’s South and West sides and into the downtown lasted days. Eventually the state militia was deployed to restore order. Though records vary, the final Chicago casualty count listed 38 fatalities (23 Black, 15 White), 537 injured and upwards of 1,000 Black families made homeless by the burning and rampant destruction of African American neighborhoods.

Likely the single deadliest incident of the Red Summer occurred in and around Elaine, Ark., on Sept. 30 and Oct. 1, after a white law officer was killed in a shootout outside a Black sharecropper gathering. Gov. Charles Brough ordered 500 Army soldiers from nearby Camp Pike to march on Elaine and put down what was labeled an “insurrection” among the Black sharecroppers. Estimates vary as to how many African Americans were killed, but upwards of 200 are believed to have lost their lives.

It’s impossible to say exactly how many people were killed or injured in the race riots and lynchings of the Red Summer of 1919—official records for some incidents were poor or never documented. We know that hundreds of people lost their lives, thousands were injured and many more were forced to flee their homes. Yet one legacy of 1919 was the growing confidence and desire to fight back—in the streets, in the courts and in the voting booth—for African American communities across the country.

The Red Summer saw Black populations fight back aggressively against racial violence and intimidation in ways that were not typical before. The Red Summer of 1919 did not intimidate African Americans into submission, as their tormentors had hoped. Instead, African Americans emerged from the violence of that bloody year with a greater sense of shared purpose, identity and pride, which served as a vital foundation for the civil rights movement to come.