Like it did for tanks and gas masks, the First World War spurred scientists and engineers to make advancements in the field of “lighter-than-air” technology – balloons. They weren’t the first to weaponize this form of aircraft, but they did create balloons that were bigger, more formidable, and capable of doing more than ever before.

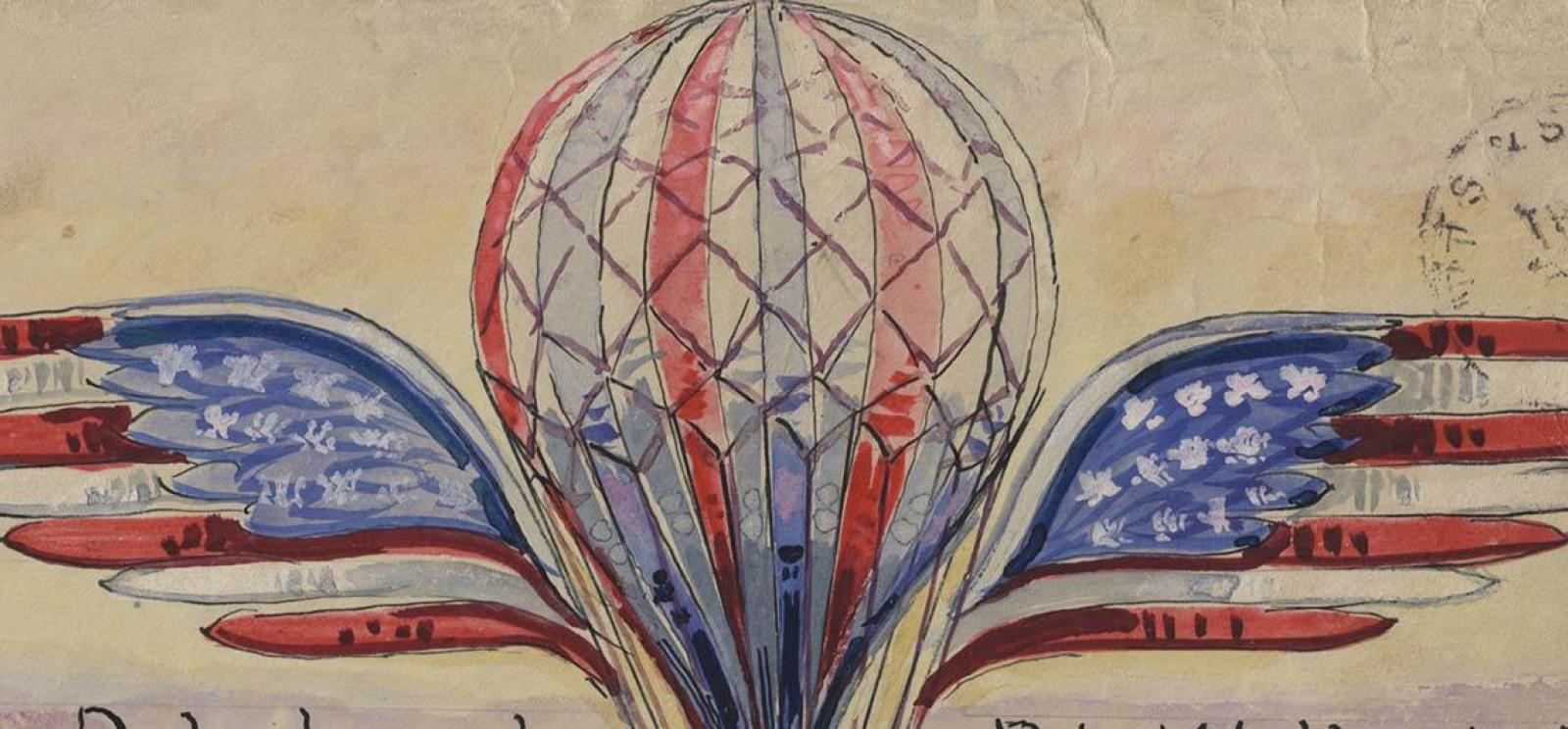

The oldest and earliest means of human flight, balloons floated in French skies for more than a century before war on the Western Front. First demonstrated in September 1783 to the court of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, the invention by brothers Joseph and Étienne Montgolfier ascended with hot air from fire. Physicist Jacques Charles increased the duration and range of balloon flight months later using hydrogen, still the preferred fuel during World War I. Balloons quickly captured the curiosity of spectators across the globe and soon proved an efficient tool for both scientific exploration and warfare.

Three types of balloons were deployed in warfare: free balloons, captive balloons and large dirigibles. While free and captive balloons were used in war as early as the French Revolution, dirigibles were introduced during the Great War. Rising at average altitudes between 1200-1800 meters above the front lines, balloons were primarily sought for reconnaissance missions; from such steep heights, balloon observers could watch their enemies’ movements on the battlefield out of range of ground fire.

Free balloons, untethered as the name implies, moved freely with the wind and could not be easily controlled. Unreliable for surveillance, free balloons functioned better as vehicles for propaganda, used by the Allies to scatter leaflets like confetti over enemy lines in Verdun and along the St. Mihiel Salient. According to Captain Heber Blankenhorn, Chief, Propaganda Section, G-2, GHQ, AEF, “there is no doubt whatever that next to the airplane the free balloon is the best medium of distribution.”

Warring nations on all sides used captive balloons to gather information on their enemies’ positions and activities. Captive balloons performed much like kites – they were tethered to a winch, a vehicle with a large spool of cable attached to the back. They flowed steadily with the wind, but in the preferred direction of a ground operator. Their average range of visibility from the air was nine miles, though when using the most advanced binoculars of the time, it could increase to a little over 11 miles. Ideally, the aim was to maneuver balloons at least six miles up the front line, but in reality, distances depended on the proximity of friendly and enemy artillery. In late September 1918, a captive balloon of the 8th Balloon Company of the AEF flew 20 miles forward – considered a world record in its time – during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

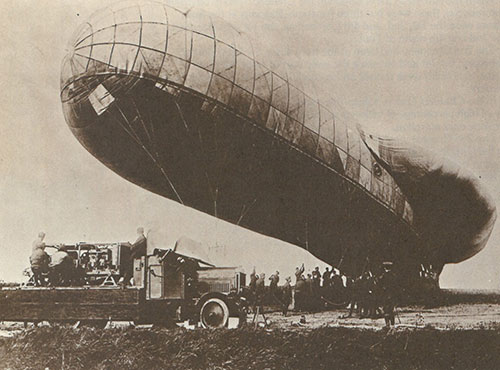

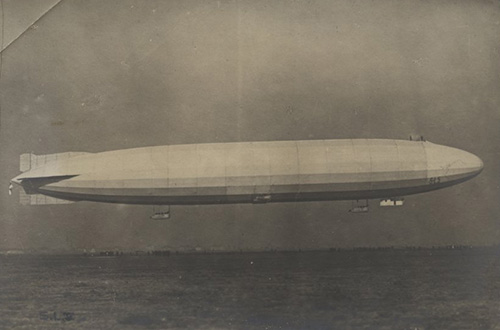

Large dirigibles, powered by engines and steered with propellers, looked and operated differently from traditional balloons. Their envelopes stretched between 600-700 feet long over varying types of frames: non-rigid, semi-rigid or rigid. Given their gargantuan size, they moved slowly. This meant they could hover in one place for a long period of time – over both land and sea – and thoroughly document the landscape during reconnaissance. (Their large size also made them easy targets for airplanes.) They could carry a larger crew of balloon observers and their equipment, machine guns and at least two tons of bombs. And so dirigibles, particularly Zeppelins, became weapons.

Balloons could travel with their companies while inflated, though typically only after surveying the route beforehand. Trees, narrow streets and high buildings could clog a balloon or tangle its cords and delay the companies’ arrival time to their destination. Given the inconvenience and the risk of being spotted, crews would deflate, disassemble and transport them by automobile instead.

“[D]aily under the brisk, resounding commands of the balloon sergeant, we learned how to take a balloon from the hangar, give her daily exercise in the clouds and return her for a night’s repose. Here we learned that a balloon is more temperamental than a prima donna or a movie actress. Day and night a guard must be kept near her chamber, with one eye on the manometer glass and another on the lookout for any careless wanderer who might sit on a pile of gas cylinders to enjoy a cigarette.”

— Excerpt from the History of the Fifteenth Balloon Company, The Balloon Section of the American Expeditionary Forces

The first four companies of the Balloon Section of the American Expeditionary Forces arrived in France on Dec. 28, 1917. Specialists from the French balloon companies that had been relieved from the Front with the arrival of the Americans conducted inaugural battle training. For future instruction, the AEF established a balloon school in France.

Along with training, the French also provided American balloon observers and maneuvering officers with most of their equipment. Up through the signing of the Armistice, American balloon companies exclusively operated the French Caquot, a double-engine winch considered the best of its time. Over time, the U.S. government sent 265 balloons and thousands of tons of raw materials for hydrogen production to French plants.

In November 1918, American balloon companies reported having only 40% of their allotted transportation, challenging their efforts to travel and complete assignments. Due to the low number of soldiers in the Balloon Section, many companies were overworked; from the time the 2nd Balloon Company arrived on the Front in February 1918 until November 1918, it had only been relieved from the front lines once, and for only one week.

“From September 26 to November 11 we lived under the most trying conditions without any relief. Weeks passed when we were working and sleeping in mud six inches deep. During those trying days it was seldom that we were dry. Two French balloon companies and one American company were put out of action of account of sickness, but we managed, probably through luck, to stick it out.

Maneuvering was very difficult as the traffic on account of road conditions was very congested. One night is well remembered by the men. We began a new move forward late in the afternoon but as traffic was jammed, we succeeded in covering only about one-half the distance to our position. For several hours we waited for an opening in the traffic but none came.”

— Excerpt from the History of the Second Balloon Company, The Balloon Section of the American Expeditionary Forces

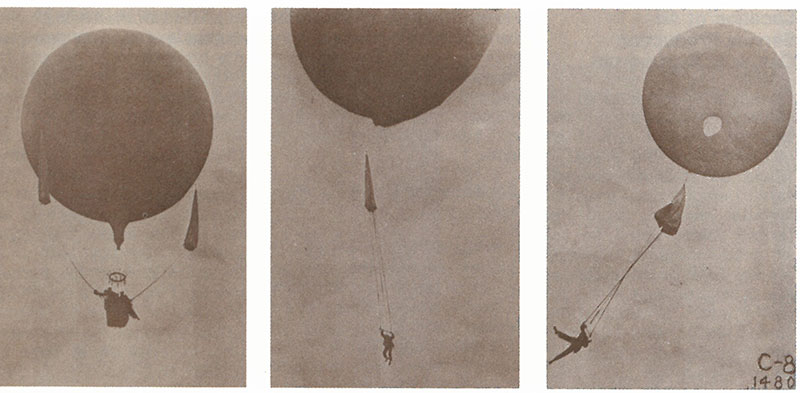

In total, there were 35 American balloon companies in France during World War I; they ascended 5,866 times, adding up to 6,832 hours in the air. Their balloons were attacked 89 times; 35 burned, 12 were shot down by enemy fire and one floated into enemy lines. Of all 116 parachute jumps from balloons, the parachutes – made of silk – never failed to open, though one observer lost his life when pieces of a burning balloon fell on his descending parachute. The reconnaissance of these balloon observers was invaluable, sighting thousands of instances of enemy planes, infantry and artillery fire.