“The Zeppelins have been to Sandringham, but the King and Queen had left a few hours earlier. No panic; people are reconciled to the fact that these visits will be repeated, and the effect they are having is no greater than that of a railway accident. It is a mistake to think that the morale of this country can be subdued. While this lasts people are laying bets for and against Zeppelins.”

— Ex-French Empress Eugenie, widow of Napoleon III, in England, January 1915

The rigid airships launched and operated by the Imperial German Naval Airship Division not only displayed the recent innovations of air bombing but also heralded the advent of total war, where the battlefields now spilled over into civilian lands and lives. Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin formed a company in 1896 for the “Promotion of Airship Flight.” With the outbreak of WWI, the airships named for him became a major weapon of war.

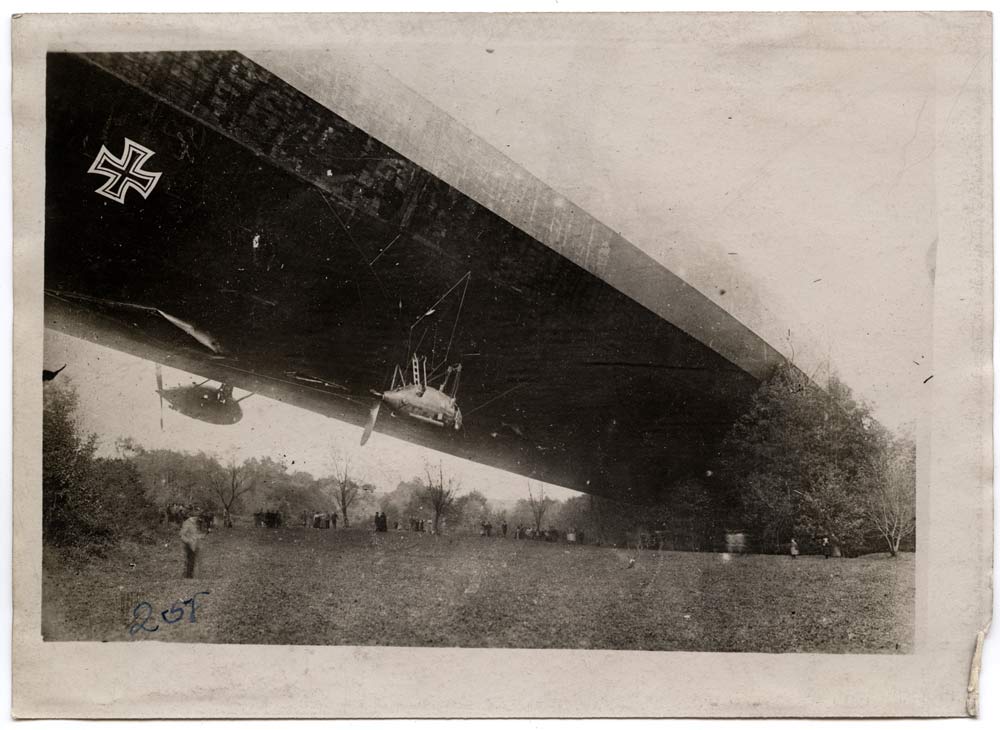

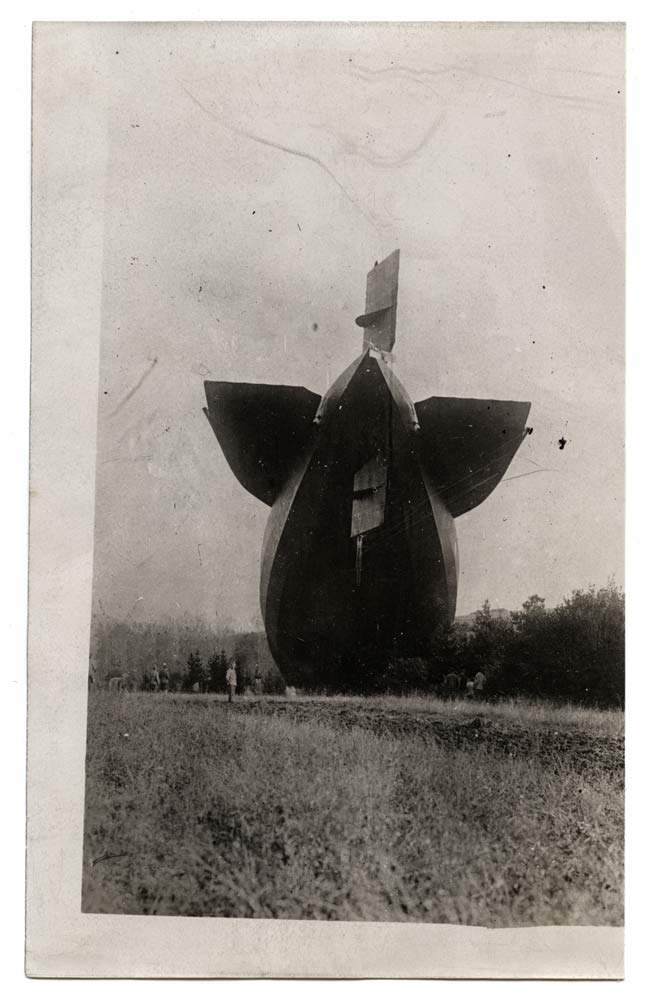

A recent addition to the Museum and Memorial’s collection is a small fragment of fabric from the skin of the mighty Zeppelin L49, one of only two items from a Zeppelin in the Museum’s collection. On the morning of Oct. 19, 1917, 13 Zeppelins, including L49, were ordered to “attack middle England. Industrial region of Sheffield, Manchester, Liverpool, etc.” With a crew of 19 and carrying 11,000 pounds of fuel, it set out with a payload of 4,410 pounds of bombs, of which 42 bombs were dropped. Following the raid, L49 was forced down in France near Bourbonne-les-Bains by French fighter planes. All crew members survived and were taken prisoners.

The American soldier who brought this fragment back as a souvenir wrote on it that it was acquired in Paris, France, Nov. 13, 1918, two days after the Armistice which halted the fighting on the Western Front. The French had dismantled the L49 to study its construction.

The Museum and Memorial archives hold a number of Zeppelin photographs, including the scenes shown here of the L49 after it was forced down.

Another artifact from a Zeppelin on exhibit in the Main Gallery is a deactivated thermite bomb. There are only a few WWI-era thermite bombs known to still exist because their very purpose was to burn up, starting fires at their targets.

“The bomb is generally filled with thermite, which upon ignition generates intense heat and by the time of the concussion has taken the form of molten metal of the extraordinarily high temperature of over 5000 degrees F. [Fahrenheit, or 2,760°C] The molten metal is spread by the concussion. The fumes of the bombs are generally very pungent.”

— Thermite bomb description from The Illustrated War News, June 2, 1915, London.

For additional reading we recommend The Zeppelin in Combat by Douglas H. Robinson, published in 1994.