And then, on Aug. 27, influenza returned to American shores. Erupting in Boston in late August, the disease exploded almost simultaneously in Freetown, Sierra Leone and Brest, France. A second wave of the global influenza pandemic had arrived. Highly contagious, this new influenza reached from coast to coast in just a couple of months and infected roughly one in four Americans. This new incarnation was also unusually deadly, with a death rate twenty-five times that of the familiar seasonal flu. Though it generally passed through communities in a couple of months, a third wave of influenza followed later that winter and spring, throwing communities into renewed chaos.

In the end, some 675,000 Americans died—more than half a million more than would normally die yearly of the flu— and as many as 50 to 100 million people perished worldwide. Adding to the social and economic disruption, almost half of those who died were between the ages of 20 and 40, leaving shattered families in their wake.

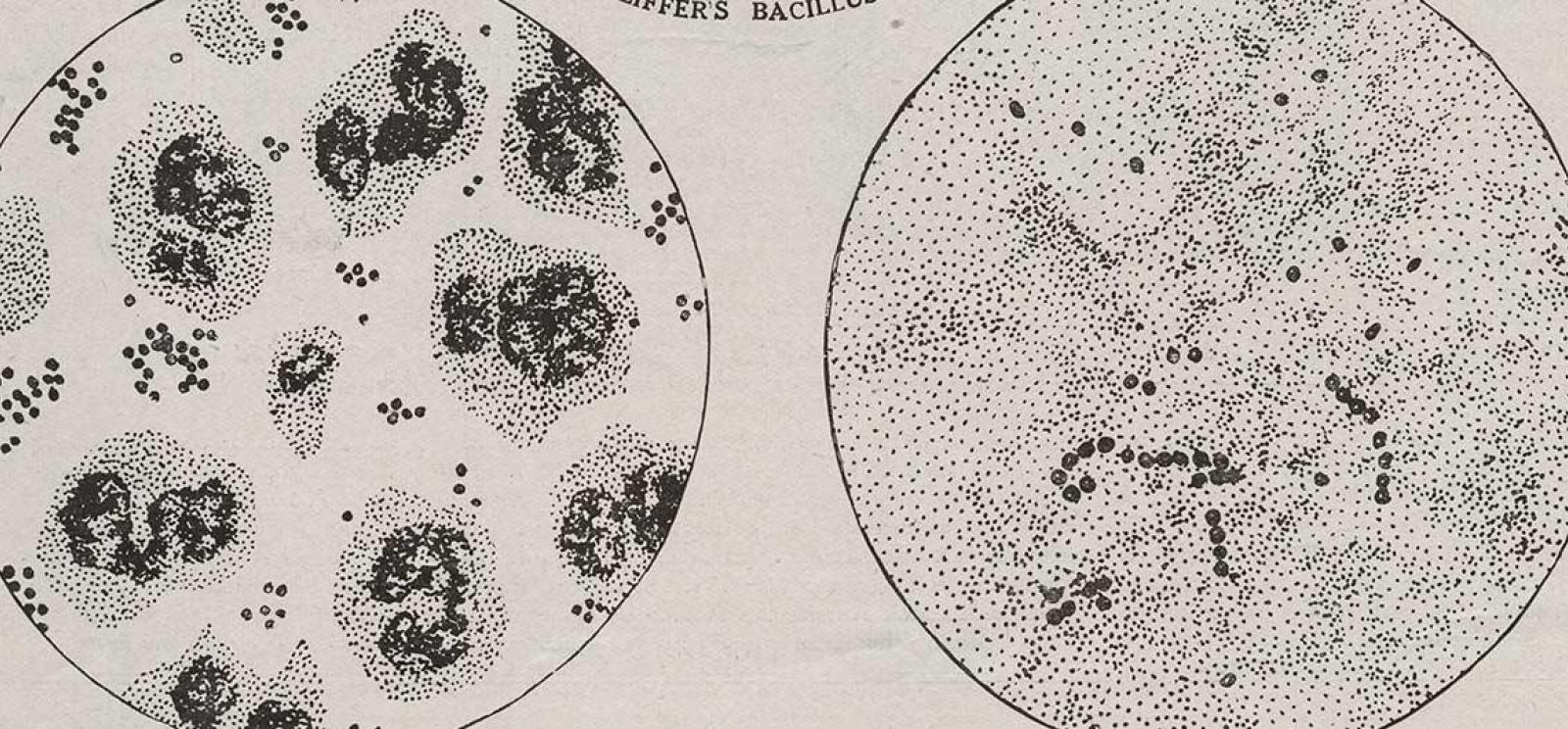

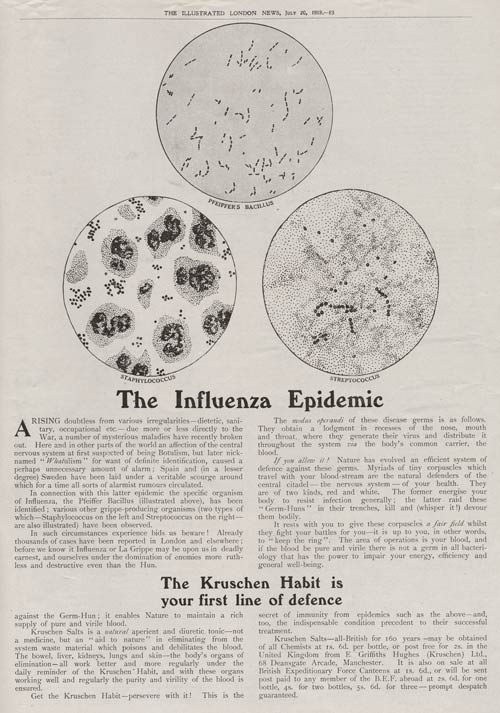

Americans were shocked by the pandemic’s destruction. During the nineteenth century the bacteriological revolution had allowed scientists to identify the causal agent of several of the most costly infectious diseases, including for instance dysentery, malaria, scarlet fever, typhoid, bubonic plague, yellow fever and whooping cough, offering the potential for preventative vaccines, and perhaps even treatments. On the eve of the pandemic, scientists, physicians, and public health experts had begun to imagine a world free of infectious disease. As the New York City Health Department declared, “Public health is purchasable.” The pandemic would prove such a vision was premature.

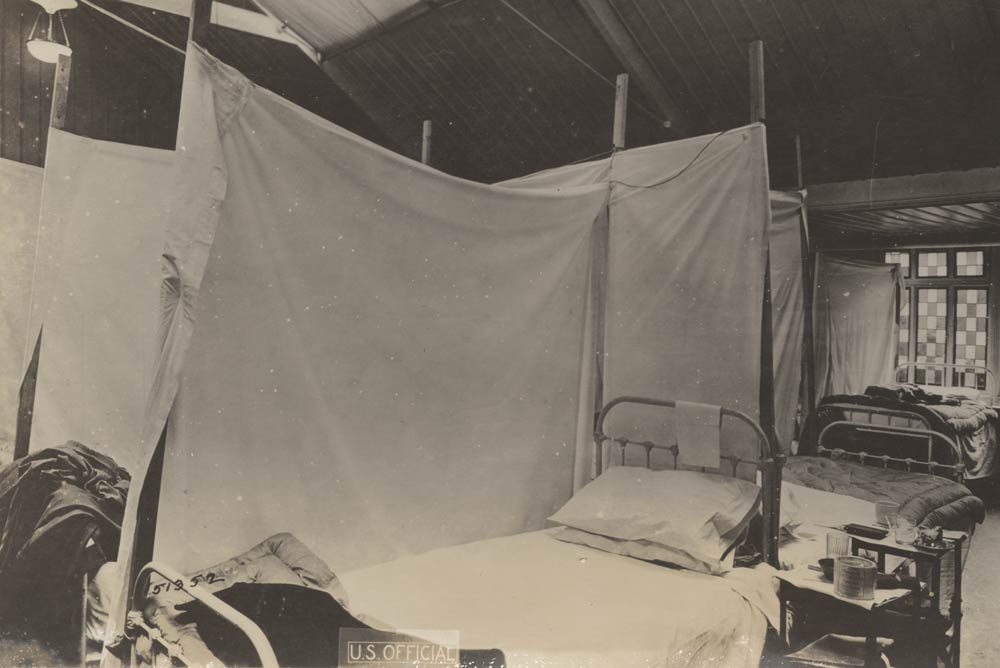

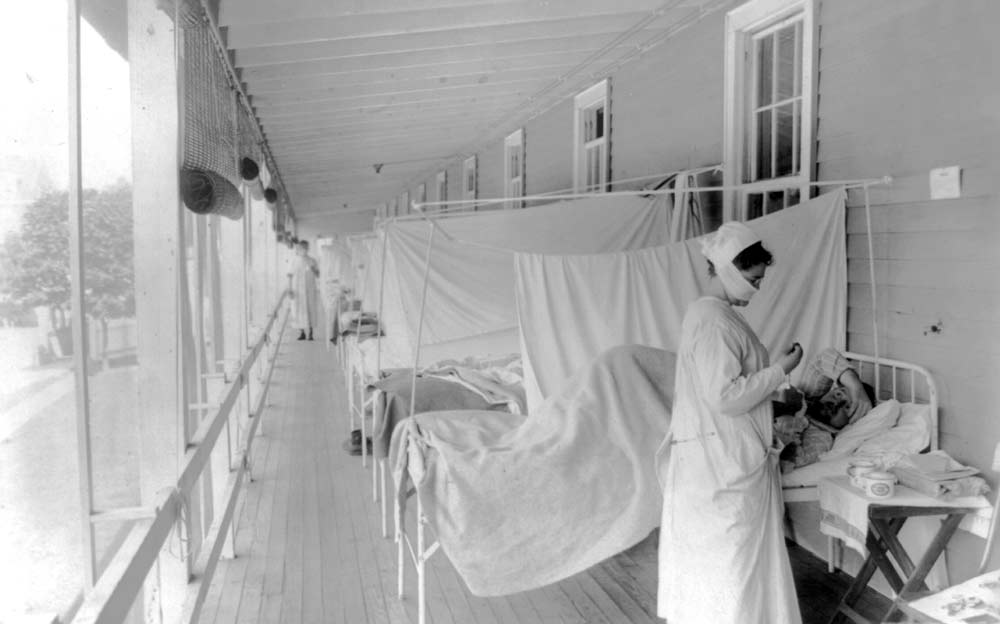

As the epidemic took hold, public health experts hurried to offer advice to government officials and education to the public. The United States Public Health Service published six million copies of a pamphlet, “Spanish Influenza” “Three-Day Fever” “The Flu,” and the Red Cross put out its own pamphlet in eight languages. The public health infrastructure, though, was still in its infancy in the United States. Decisions about emergency measures were in the hands of state and local public health officials whose power and expertise varied widely. So also would their approaches to the crisis and their communities’ resulting experiences.