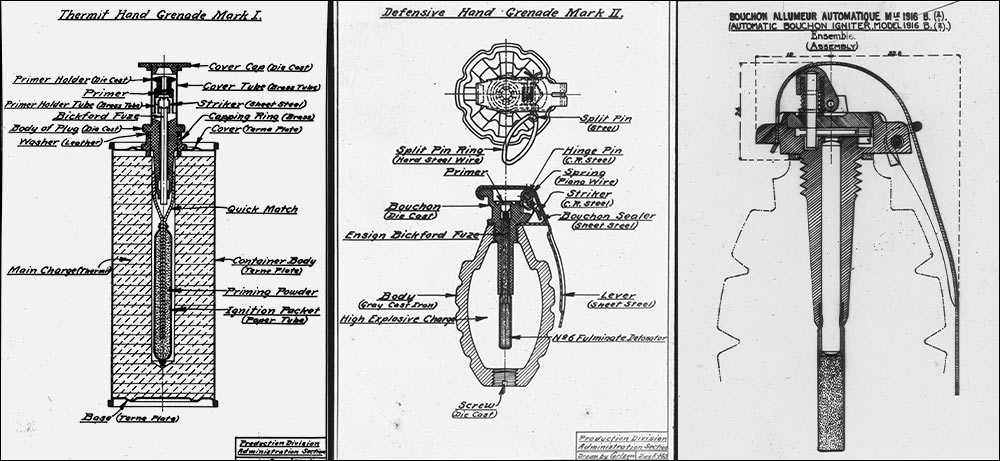

In World War I, hand grenades were also known as “hand bombs.” The general philosophy for their use in the fighting armies was that grenades could kill the enemy underground or behind cover. They could also force the enemy into the open, providing targets for rifle and machine gun fire.

Offensive grenades used concussion, or shock-waves, to wound, while defensive grenades exploded, scattering shell fragments. Gas, smoke and illuminating grenades were also used in World War I. These grenades were made of brass, iron and steel, some with handles of wood and even cardboard. They went by many names: Battye bombs, Citron Foug, Newton-Pippin, Petard, Besozzi, Kugel, Cigaro and Sigwart; and took on many shapes.

The term “grenade” comes from the Latin, granatus, literally “filled with grain.” The “grain” in grenades was explosive mixtures and compounds contained in metal canisters and set off by spark, fuse, mechanical or percussion ignition. Some sources relate that the term is derived from the Spanish word granada or pomegranate, for the resemblance between the fruit and the weapon. When grenades first came into use in warfare is unknown. But legend has it that the first grenade was a small box of live vipers (snakes) which ancient warriors threw into the enemy’s camp.

The first recorded use of the word “grenade” came in 1536, from the siege of Arles in southern France by French forces under King Francis I. The early grenades were made of glass globes, jars, kegs and firepots. A 1665 reference related that grenades were carried in a pocket called a grena-diere.

By 1667, the French army had regular companies of grenadiers. Grenades did not play a large part in warfare, although the French used some 3,200 of them at Sebastopol in 1854-55, and got some Russian ones in return. Some were used in the American Civil War, but they came into prominence in the Russo-Japanese war, just a decade prior to WWI. The Russians established three factories in Port Arthur, China to turn out a thousand grenades a day.

On that fateful day of June 28, 1914, when the Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were assassinated, several of the Black Hand conspirators carried and used Kragujevac hand bombs, named for the Serbian army depot. Their explosions caused a verbal explosion from the Archduke Franz Ferdinand to the Mayor of Sarajevo after early attempts on his life “What is the use of your speeches? I come here to pay you a visit, and I am greeted with bombs. It is outrageous!”

At the start of the war the Germans only trained special infantry troops, or “pioneers,” to use hand grenades. Soon two types of grenades became standard for the Germans: stick (with the explosive can attached to a wooden handle) and egg (because it resembled an egg). German stick grenades were also called “potato mashers” again for their shape.

Early in the war, the French were not prepared for the use and production of grenades. One report in January 1915 stated that while the soldiers were completely lacking in factory-produced grenades that they were not lacking in ingenuity in fabricating remarkable projectiles made from canned beef, sardines, tuna and foie gras cans. After eating the delectables they took the cans, loaded them with stones collected from the trenches, shrapnel balls and explosive materials of all sorts, and inserted wick fuses that lasted less than 6 seconds.

The early British front-made grenades were similar to the French, although few were as exotic as foie gras cans. They were mostly jam pots. British development of rifle grenades early in the war was fragmentary. The rod was inserted down the barrel of the service rifle and launched with a special blank cartridge. Rifle grenades were designed to land head-first, but often failed to do so. They carried high explosives, smoke, signals and messages. Late in the war, anti-tank rifle grenades were developed.

British brigade orders issued for the Somme attack on July 1, 1916, stated that the grenade or bombing squads: each non-com would carry 6 mills bombs, 4 rifle grenades and 2 smoke; the 2 bayonet men would carry 12 mills bombs and 4 smoke; the 2 throwers carried 24 mills and 4 smoke; the 2 carriers (reserve throwers) carried 24 mills and 4 smoke and the 2 rifle grenadiers carried 8 mills and 20 rifle grenades for a total of 74 mills bombs, 24 rifle grenades and 14 smoke grenades.

The Russians utilized a small variety of grenade types. There is a Russian Model 1914 hand grenade, dated 1914. Made of sheet metal attached to a wooden handle, the square head resembles a lantern, thus its nickname. The Russian Model 1914 was also called a “bottle” grenade for its shape.

The U.S. Army War College in early 1917 described the development of grenades in the war: “Grenades used in the early part of this war were improvised on the field of battle, but the success obtained by their use led to the invention of many new standard types and their subsequent adoption by all modern armies.”

Many grenades types were used by American troops. The main ones utilized were the American Mark I, French VB rifle grenade with discharger, French Model 1916 Smoke and suffocating grenade, British Type No. 27 combination hand and rifle grenade (white phosphorus), French Model 1916 Lachrymatory and Irritating Grenade and French Model 1916 incendiary grenade.

Whether factory-produced or made in the field from sticks of dynamite and shrapnel balls, hand and mechanically launched grenades had established their place in modern technological warfare. A long way from a box of vipers.