In his war address to Congress on April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson spoke of the need for the United States to enter the war in part to “make the world safe for democracy.” Almost a year later, this sentiment remained strong, articulated in a speech to Congress on January 8, 1918, where he introduced his Fourteen Points.

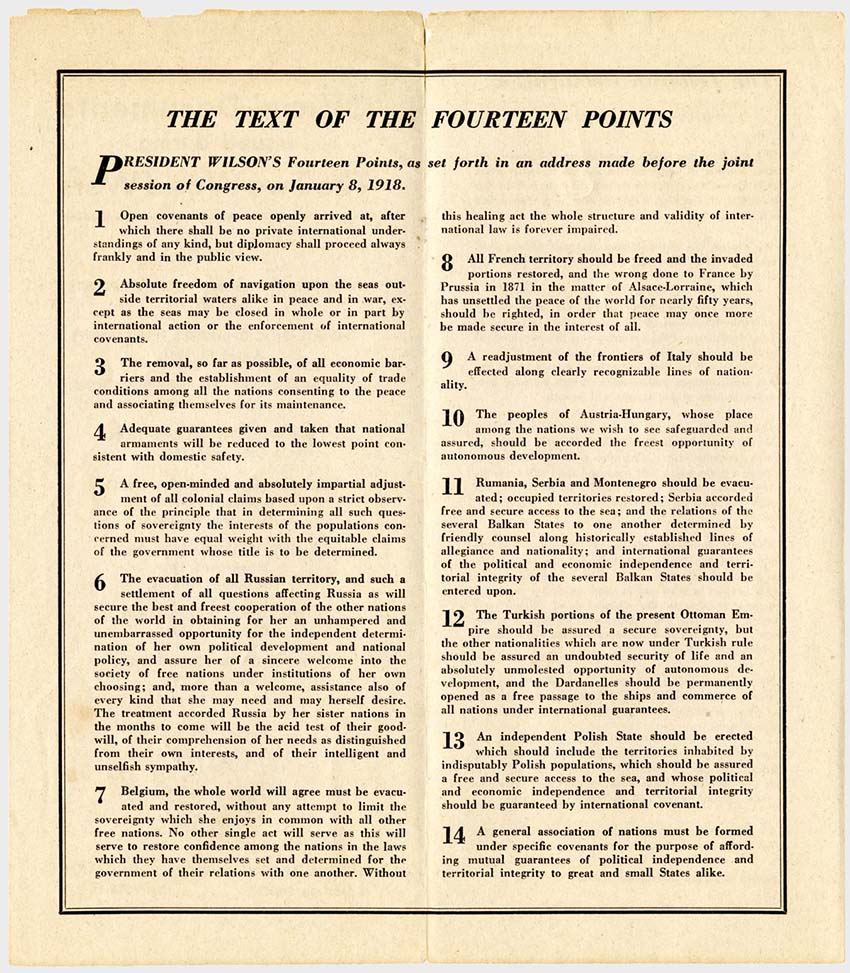

Designed as guidelines for the rebuilding of the postwar world, the points included Wilson’s ideas regarding nations’ conduct of foreign policy, including freedom of the seas and free trade and the concept of national self-determination, with the achievement of this through the dismantling of European empires and the creation of new states. Most importantly, however, was Point 14, which called for a “general association of nations” that would offer “mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small nations alike.” When Wilson left for Paris in December 1918, he was determined that the Fourteen Points, and his League of Nations (as the association of nations was known), be incorporated into the peace settlements.

The Points, Summarized

1. Open diplomacy without secret treaties

2. Economic free trade on the seas during war and peace

3. Equal trade conditions

4. Decrease armaments among all nations

5. Adjust colonial claims

6. Evacuation of all Central Powers from Russia and allow it to define its own independence

7. Belgium to be evacuated and restored

8. Return of Alsace-Lorraine region and all French territories

9. Readjust Italian borders

10. Austria-Hungary to be provided an opportunity for self-determination

11. Redraw the borders of the Balkan region creating Roumania, Serbia and Montenegro

12. Creation of a Turkish state with guaranteed free trade in the Dardanelles

13. Creation of an independent Polish state

14. Creation of the League of Nations

President Wilson’s insistence on the inclusion of the League of Nations in the Treaty of Versailles (the settlement with Germany) forced him to compromise with Allied leaders on the other points. Japan, for example, was granted authority over former German territory in China, and self-determination—an idea seized upon by those living under imperial rule throughout Asia and Africa—was only applied to Europe. Following the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, Wilson returned to the United States and presented it to the Senate.

Although many Americans supported the treaty, the president met resistance in the Senate, in part over concern that joining the League of Nations would force U.S. involvement in European affairs. A dozen or so Republican “Irreconcilables” refused to support it outright, while other Republican senators, led by Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, insisted on amendments that would preserve U.S. sovereignty and congressional authority to declare war. Having compromised in Paris, Wilson refused to compromise at home and took his feelings to the American people, hoping that they could influence the senators’ votes. Unfortunately, the president suffered a debilitating stroke while on tour.

The loss of presidential leadership combined with continued refusal on both sides to compromise, led Senate to reject the Treaty of Versailles, and thus the League of Nations. Despite the lack of U.S. participation, however, the League of Nations worked to address and mitigate conflict in the 1920s and 1930s. While not always successful, and ultimately unable to prevent a second world war, the League served as the basis for the United Nations, an international organization still present today.