“I saw a letter from one of the fellows who went back on the same boat as the ‘Honeymoon Detachment’ and he told of the fights the French & Germans [war brides] had. They had trouble all the way back. We only sent seventeen back in the last boat but I have over fifty ready for the next one. I think that from now on they will send a man back as soon as he begins to consider marrying over here. They ought to.”

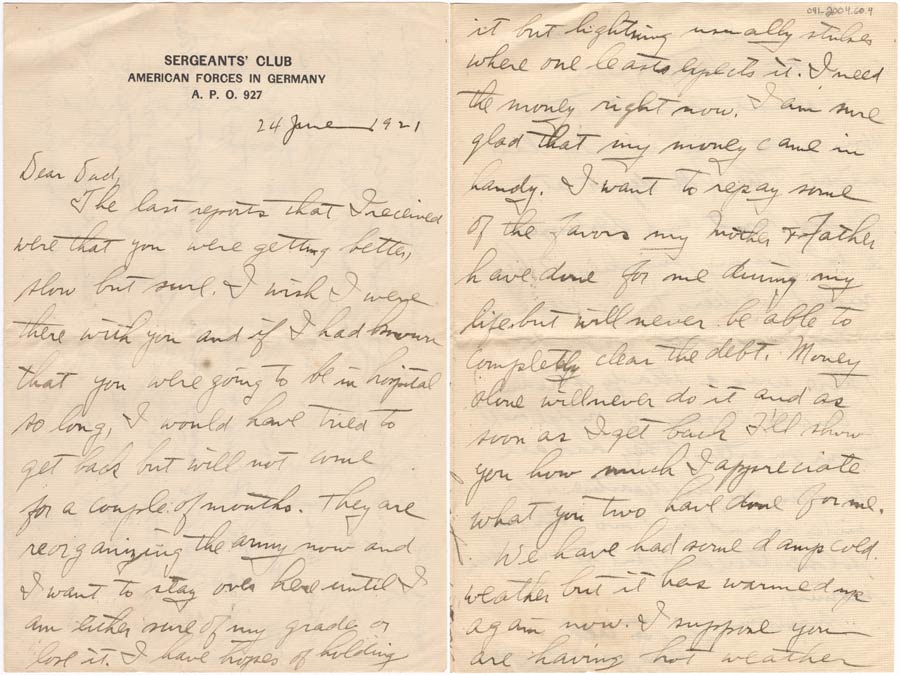

— Sergeant Phillip Kent, writing to his father, June 24, 1921

When Sergeant Phillip Kent wrote this letter, it is easy to assume that his family found it amusing. After all, French and German war brides fighting neatly mimics the Central Powers and Allies during the war. However, a deeper reading of Sergeant Kent’s letter also reflects his negative feeling about war brides and their American husbands, a feeling that was common after the war. Sergeant Kent served with Casual Depot No. 42 in Coblenz, Germany with the Army of Occupation. A collection of his letters in our archives highlights many aspects of the Army of Occupation in Germany between 1919-1923, including the often-overlooked war brides of World War I.

The term ‘war brides’ originally referred to women who quickly married before their husbands left for military service. By the end of the Great War, war brides took on the entirely new meaning of international women marrying American soldiers serving overseas. Intercultural unions between American soldiers and local woman were not a new phenomenon, with the first marriages occurring during the Spanish-American War 20 years prior. However, with thousands of marriages, World War I was the first war with formal regulations enacted to control these relationships.

General Pershing and the AEF command quickly discovered that these marriages were deemed controversial and affected many opinionated groups. In the United States, President Woodrow Wilson expressed concern that these marriages would tar the AEF’s image as the “cleanest” army in the world. American families were also concerned that “loose” and “immoral” French woman would take advantage of their innocent boys. One mother, worried about the “impure” influences that soldiers would be exposed to during their service, wrote to Secretary of War Newton Baker, “We are willing to sacrifice our boys, if need be … but we rebel and protest against their being returned to us ruined in body and ideals.”

The French government and its citizens took offense to this characterization of French women. Families also feared their daughters would be abandoned by American soldiers. After considering all these voices and more, General Pershing issued information regulating marriages in Bulletin No. 26 on March 29, 1919. The bulletin includes information from the French Minister of Justice and lists the information needed to marry which includes the soldier’s name, his parents’ names and whether he was divorced.

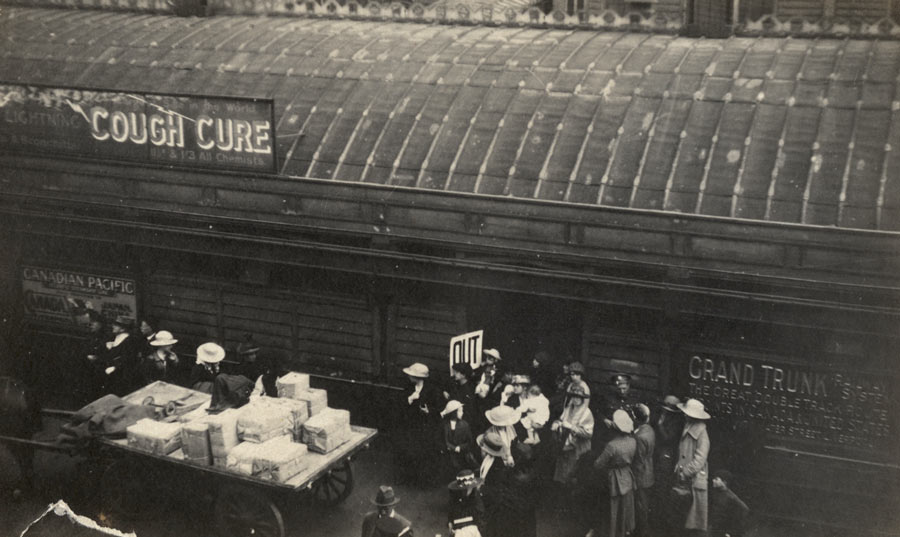

Once these regulations were in place, the AEF encountered the issue of transporting the new families home. Three holding camps were formed in France to accommodate the war brides and their children. The camps ran with military efficiency and the women were subject to morning inspections, a physical examination to insure they were free of venereal disease and a final baggage check to make sure bombs or explosives were not being brought into the United States. The baggage check came courtesy of the first communist Red Scare running rampant in the U.S. at the time.

While the conditions of the camps could be challenging for the women, the government attempted to prepare the new brides for their lives in America. The War Work Council of the Y.M.C.A. offered classes in the camps including English language, geography, American laws, customs, and cooking.

The soldiers, welfare workers and other personnel that assisted the war brides had mixed feelings about these new U.S. citizens and this was reflected in their correspondence. Sergeant Phillip Franklin Kent served with Casual Depot No. 42 in Coblenz, Germany with the Army of Occupation. Sergeant Kent organized transport home for American soldiers, including war brides and their children. His letters leave the impression he did not think highly of the war brides, a sentiment echoed by many in the United States.

Writing to his mother on Aug. 17, 1921:

“If they put off sending married men home for two months, we will have another ‘honeymoon special’ to send. I have something like seventy five married couples ready to send to the U.S.A. now. There is a wife of a soldier in here now with her two children. She is a widow and has two children, one: 13 yrs old and the other 9 yrs. Looks as though that soldier has a good sized family to take care of already and he was married last month. I don’t understand what these soldiers are thinking of when they marry some of these frauleins. It is wasting time to even talk about them.”

While many Americans agreed with Sergeant Kent, many others welcomed the war brides. Camp newspapers created by American soldiers include numerous announcements of these marriages, and offered encouragement to the new couples.

An article published in 1921 provided a happy update on Elsie Marie Norton, a French war bride then living in Kansas City, Kansas:

“Today you can find Elsie Marie…singing happily as she busies herself about the household duties. And as for America and her hero-husband – she loves them both ‘beaucoup.’”

The American Legion Weekly went even further and encouraged Americans to welcome these new citizens with open arms:

“These girls in their own way are as brave as the men they married. Each left home to fare in a country whose manners and customs, ways of life and thought, are strange to them, In the case of the French girls they must learn a new language. Each community or neighborhood in which they are to reside should bid them welcome and accept them with a spirit of true hospitality, which embraces sympathy and understanding.”

While we do not know the exact number, research shows that between 5,000 to 18,000 women immigrated to the United States after World War I as war brides from Belgium, England, Ireland, France, Russia, Italy and Germany. The quotes from Sgt. Kent’s collection highlights that these unions were often difficult. However, war brides also benefited from loving, secure unions and gained acceptance in their communities.