“Really we are astonishingly patient. Of course we ‘grouse’—it has always been the unquestioned privilege of the British Army to do so, and we like to keep up the old traditions. ‘Grousing’ clears the air like a summer storm, without doing any harm. An army with ‘no complaints’ would be a suspicious, dangerous thing… But it is the little unimportant things about which we grouse: the unequal distribution of the rum ration, the maddening buzz of the mosquito, the accidental breaking of a favourite pipe, the vagaries of the Macedonia climate, the sinking of a parcel mail.”

“….we are at war with Bulgaria by accident. We try just as hard to exterminate the Bulgar as the Hun: because we are thorough, and we realize that it is futile to wage war by halves. The chance alliances of war have thrown certain Balkan States on our side and others against us. It is therefore our duty to support our Allies and to overcome our enemies.”

— Salonica Side-Show by V.J. Seligman, 1919

Following a series of treaties signed with Austria-Hungary on Sept. 6, 1915, Bulgaria joined the Central Powers alliance and attacked Serbia, an Allied power, on Oct. 5, officially declaring war on Serbia on Oct. 12. In an effort to support Serbia and keep Bulgaria out of the war, Britain and France transferred forces from their operations against the Turks at Gallipoli to the neutral country of Greece, landing them at the port city of Salonica on Oct. 5. By the summer of 1916, the Allies had about 600,000 men at Salonica, comprised of forces from Britain, France, Italy, Russia and Serbia. Within this multi-national army, the British Salonica Force numbered about 150,000 by early 1917.

The popular history of World War I is usually the story of the trenches and war of attrition of the Western Front in France and Flanders; sometimes it is the story of huge armies trying to out maneuver each other on the Eastern Front. However, the war’s story also contains chapters about its “side-shows” such as the campaigns in the Eastern Mediterranean—the Dardanelles, the landings at Gallipoli and in Greece at Salonica.

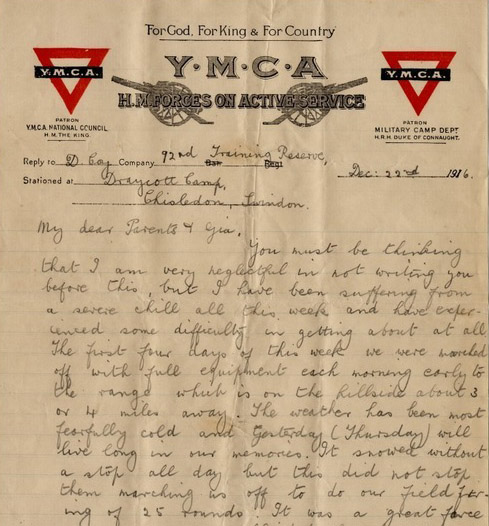

A collection of letters donated to the Museum in 2011 from the service of a British soldier in the Salonica-Macedonian theater of operations, vividly conveys the nature of this part of the war.

Thomas John Rees enlisted in the British army in 1916, having been raised on a farm in the Rhondda valley, South Wales. In 45 letters home to his parents and family, Rees describes his training as a sapper in a Royal Engineers camp in Pembroke, England, his travel through France to Marseilles where he shipped to Salonica and his service in the trenches for nearly two years.

The letters provide details about Rees’ surroundings, but as was common to all of the war’s personal correspondence, they are self-censored, as place names and travel dates could not be mentioned. He describes weather that seems to alternate between snow and sunshine and “beautiful sights such as sunset and moonrise on the Mediterranean.” He comments that the area’s population lives in small villages, mostly Macedonians and Armenian refugees.

Rees was a typical soldier serving overseas, doing his job: in his case, digging trenches and dugouts in the mountains. His homesickness comes through in his writing. He asks his family to send him cigarettes, cake, chocolates—luxuries that the Army provides of poor quality or not at all. “You cannot imagine what a great pleasure it is to receive parcels and letters from you as it is only the thought of home and loved ones that keeps us alive out here as the life is very monotonous,” Rees wrote.

The Macedonian landscape, with its “flower-dotted” mountain stream banks reminded him of Wales. He mentions that some soldiers from the Welsh regiment performed a choral concert at the YMCA tent.

His only tangible connection to home and family is his letters; his thoughts in his words sent a thousand miles home on weekly basis, but even this tenuous contact could be interrupted by the sinking of a mail ship.

Despite bouts with malaria and influenza that hospitalized him, Rees survived the war. He eventually went home to Wales, worked for a rural electric company and raised a family.

For more information about the Thomas John Rees collection or questions about the Museum’s archives or library collections please contact research@theworldwar.org.