What is a cootie? Ask a World War I soldier, and you’d get a much more serious answer about a much more serious problem than you might expect. ‘Cooties’ was the nickname American soldiers gave to body lice – the itchy little bugs that burrowed into skin, hair, clothing, blankets and just about anything made of natural materials. For many soldiers, cooties were as relentless as their human enemies.

As Captain Francis Bangs, MP Company, 77th Division, wrote in a letter home to his father:

“Unfortunately the cooties or shirt squirrels as they are vulgarly called, are not confined exclusively to the trenches and I have had many battles with them at the same time that Jerry [Germans] was dropping bombs around me and I was trying to be comfortable in a gas mask. The enemy at home is truly the more insidious. I suppose a good dose of mustard gas would kill them, but I think I will stay in the dugout just the same.”

It was a challenge to avoid cooties in the trenches. Baths and delousing stations provided relief, but those luxuries were not always available. Many soldiers resorted to laboriously picking the cooties off themselves and their clothing one at a time. British soldiers called this process of delousing “chatting,” the origin of the word “chat.” American soldiers referred to it as “reading” their clothing.

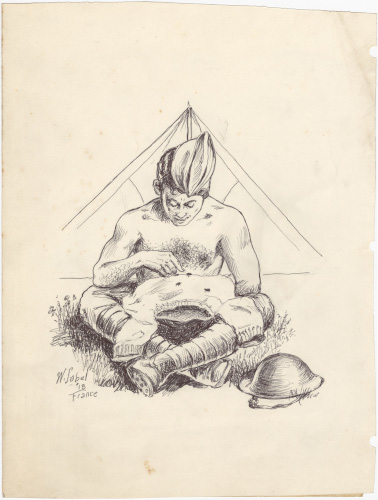

This recently processed illustration depicts an American soldier reading his shirt for cooties. Titled An Ode to a Cootie, it was drawn by Private First Class Walter R. Sabel, 108th Ammunition Train, 33rd Division.

Sabel made a few versions of this drawing. He included this poem on one copy:

Sleek little, sly little, slippery louse,

That in my shirt has set-up house;

You live in gory revelry,

And never cease your deviltry;

Until my nails launch an attack

About the region of my back.

But you can’t always hide; nor fly

Beyond the vision of my eye;

For neither fold nor sheltering seam

Can save you from a bath of steam

Sabel trained at the Art Institute and the American Academy of Art in Chicago before serving in France. Besides drawing for himself, Sabel also made portraits of fellow soldiers and sold them for two francs each. After the war, he worked as a commercial artist for more than 50 years.