On Jan. 16, 1919, after nearly a century of activism, the Prohibition movement finally achieved its goal to rid American society of “the tyranny of drink.” Passed by Congress on Dec. 18, 1917, the 18th Amendment, prohibiting “the manufacture, sale or transportation of intoxicating liquors,” was ratified and would take effect at midnight on Jan. 17, 1920.

For 13 years, the United States was officially “dry,” but from its very inception, the law was controversial and difficult to enforce, and its effect on the country’s problems with alcohol was debatable. In 1933, Prohibition came to end with the ratification of the 21st Amendment, the first and only time in American history where ratification of a constitutional amendment signaled the repeal of another.

The debate over alcohol in American society had its roots in the first half of the 19th century. By that time, alcohol had become an established and integral part of everyday life; the Mayflower carried barrels of beer in its hold, John Adams began each day with a tankard of cider, even a young Abraham Lincoln sold whiskey by the barrel. It was considered better and safer than water and was consumed by many Americans without regard to age; by 1830, the average American over 15 drank the equivalent of 88 bottles of whiskey every year.

Though a young Frederick Douglass stated that whiskey made him feel “self-assured and independent,” the intoxicating beverages had profound effects on society. The number of drunkards in workhouses and prisons increased and women and children were left abandoned and abused by inebriated husbands and fathers. By mid-century, Americans calling for the abolition of slavery, participating in religious revivals and other reformed-minded pursuits took up the call for temperance.

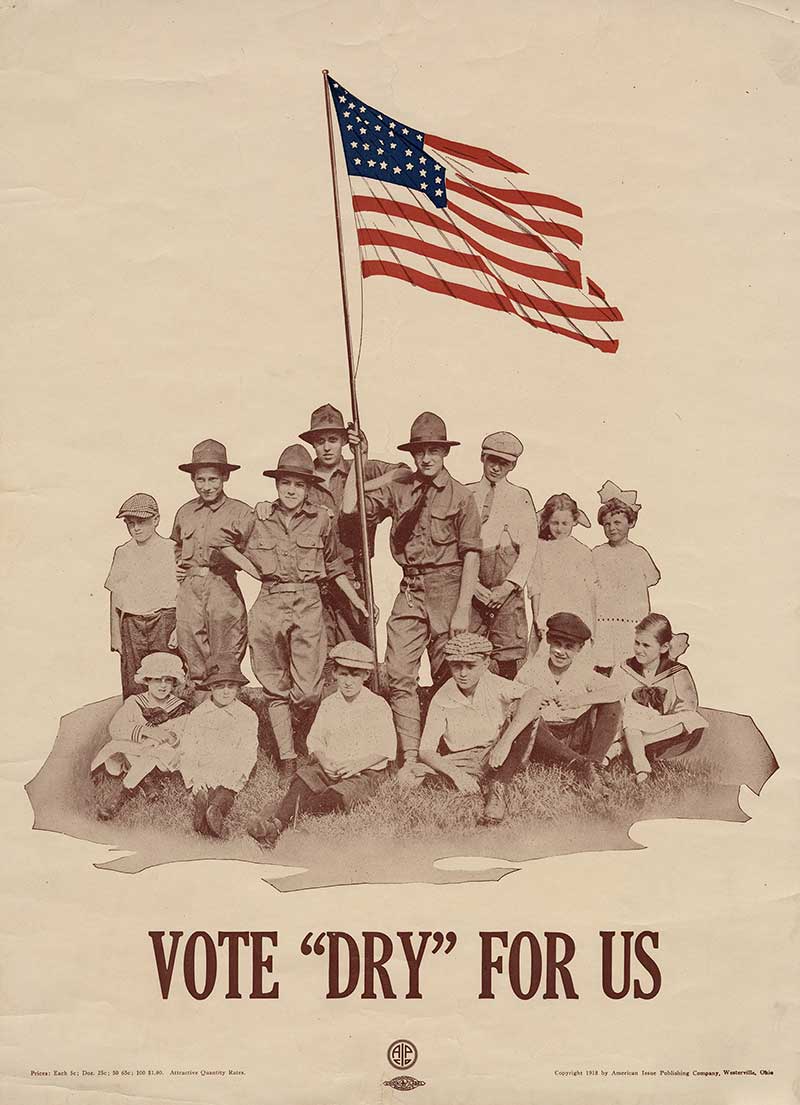

Like other reform movements, the Temperance Movement used religious language in its calls for abstention, equating alcohol to Satan and no less evil than slavery. The movement also contributed to the emerging public role of women, as the cause against alcohol, like abolitionism, was one considered acceptable for them to participate in. They formed women’s crusades, praying and singing hymns in front and inside of saloons, and in 1874, founded the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), which became one of the largest and most influential women’s organizations of the 19th century.

Some women took a more hardline approach. Kansan Carrie Nation physically attacked and destroyed saloons, viewed by temperance advocates as the preeminent symbol of the evils associated with alcohol. Hatred for the saloon, combined with the growing belief that alcohol consumption must not be tempered but prohibited, contributed to the formation of the Anti-Saloon League (ASL) in 1893. Under the leadership of Wayne Wheeler, the ASL ultimately became one of the most effective political pressure groups in U.S. history, its sole goal to rid the country of alcohol county by county, state by state, until national prohibition was achieved.

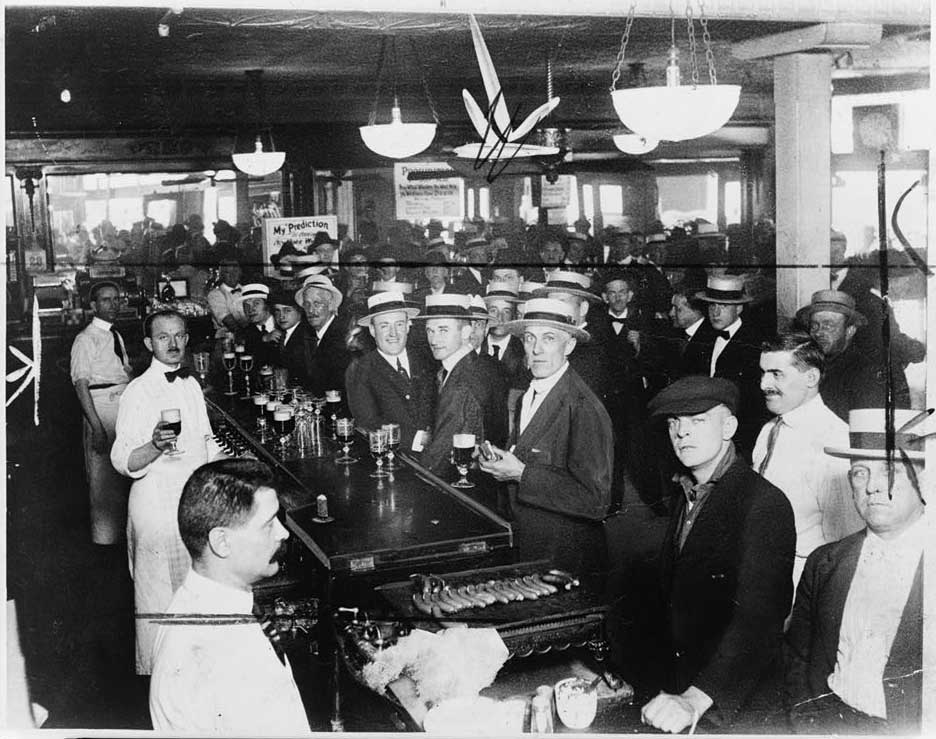

Despite the growing Prohibition movement, the number of saloons continued to increase, with around 300,000 across the country by the turn of the 20th century. For patrons, saloons were more than a bar, they were also a male congregating space where one could converse with neighbors, read newspapers and, for newly-arrived immigrants, learn the English language and/or American customs.

Breweries flourished, producing nearly 40 million barrels of beer per year as the 20th century dawned, a figure that – when taxed- constituted 70 percent of the federal government’s annual revenue. This financial dependence made brewers like Adolphus Busch, the “emperor of beer,” confident that national prohibition via a constitutional amendment would never occur. Events, both domestic and foreign, however, soon made the impossible possible.

In 1913, the 16th Amendment was ratified, granting the federal government the power to levy and collect taxes on incomes, legislation that had long been part of progressive reform, but had also been promoted by the Anti-Saloon League. By the time World War I broke out in Europe the following year, millions of Americans including industrialist Andrew Carnegie and educator Booker T. Washington supported Prohibition. State and local governments also continued to pass dry laws and President Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of the Navy and first Secretary of State were both vehemently anti-alcohol.

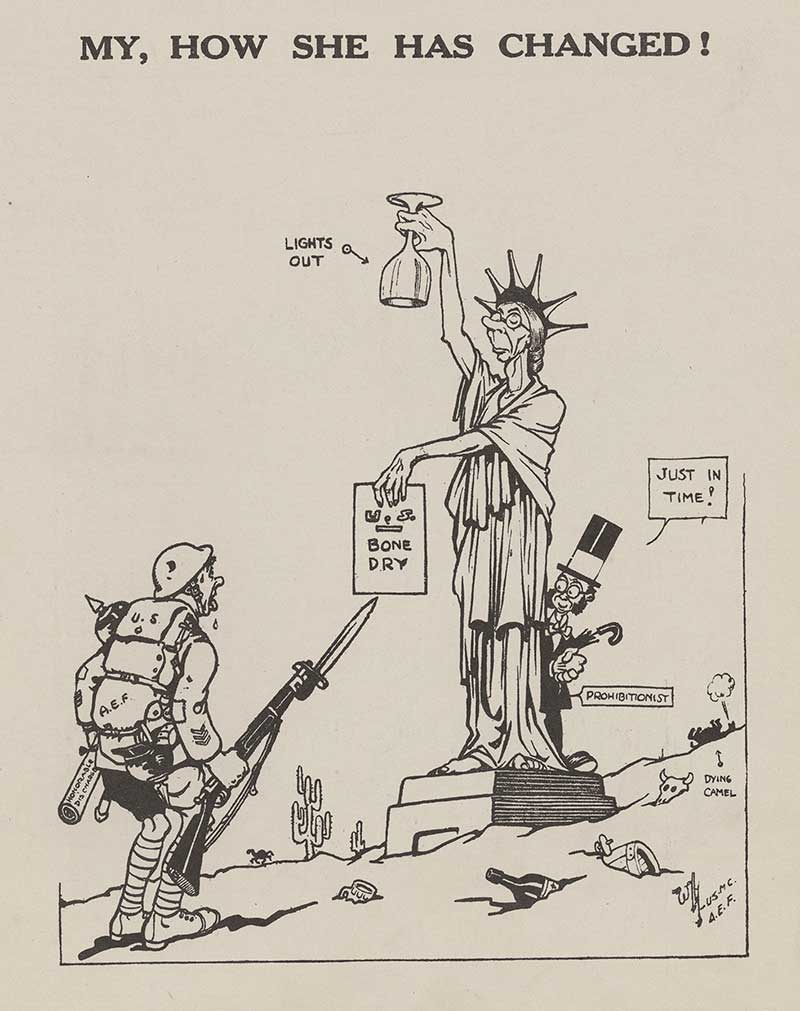

Following U.S. entry into the WWI in 1917, increased anti-German propaganda for the war effort led to popular hysteria against German Americans. This proved beneficial for the Anti-Saloon League and the Prohibition movement as most breweries were owned by German Americans,. That same year, Congress passed the 18th Amendment and it was ratified less than 13 months later. The fifth largest industry in the U.S. was now illegal, leaving prohibitionists elated, but the question remained as to whether the new law could be properly enforced.

With the onset of Prohibition in 1920, supporters were confident of its success. The power of the federal government would relieve the country of the scourge of alcohol and alcoholism, creating a better version of society. Initially, their confidence reflected reality, as public drunkenness and alcohol consumption declined, and Americans willingly complied with the new law.

The law did have loopholes that were exploited. The act of drinking was not illegal, nor was it illegal to make wine at home. Given the one-year grace period between ratification and formal enforcement, people also had had ample time to stockpile alcohol; this was especially true of those Americans with the money to do so. Farmers that grew fruit retained the ability to produce hard cider, and whiskey and wine were available for medicinal and religious purposes, respectively.

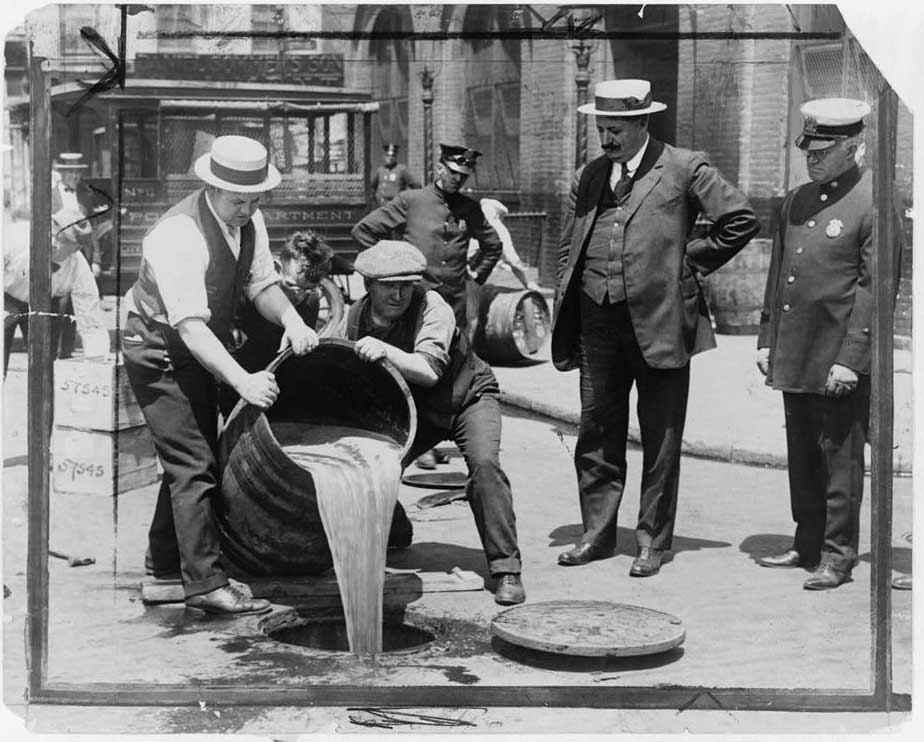

Arguably the biggest challenge to Prohibition’s success, however, was federal enforcement. From the beginning, the government lacked the agents required to uphold the law and the fiscally conservative Republican administrations of the 1920s were unwilling to appropriate the necessary funds. It also became evident that many of the underpaid commissioners tasked with closing illegal speakeasys and confiscating illegally purchased or produced alcohol were not dedicated to Prohibition, but rather were “on the take.”

States believed it was not their responsibility to assist with enforcement, thus giving ample opportunity to those who sought to flout the law. Men like Roy Olmstead of Seattle and George Remus of Cincinnati became millionaire bootleggers, while others like Kansas City’s Tom Pendergast increased their political influence by being able to keep a city “open”. Bootlegging itself spawned increased violence in cities like Chicago and New York and made criminals like Al Capone and Lucky Luciano infamous throughout the country.

As alcohol-related crime and violence escalated throughout the 1920s, some Americans began to call for an end to Prohibition, calling the 18th Amendment a “terrible mistake” and a disaster that had “created contempt and disregard for the law all over the country.” The very ideas behind the call for Prohibition—to undercut the ravages of alcohol and alcohol consumption—had now themselves been undercut by the law’s unintentional consequences. Millions of Americans had stopped drinking, but those who continued to drink drank more and drank beverages of questionable, even deadly, ingredients.

Federal agents and local police alike were unable or unwilling to completely extinguish homemade stills, allowing moonshine (homemade liquor) stillers to provide thirsty Americans and money-motivated bootleggers with a regular supply of their product. And while prohibitionists championed the death of the saloon, they were often unable to prevent the growth of its replacement, the speakeasy, where men and women socialized together while enjoying a drink and, in many cases, the period’s most famous music sensation, jazz. Despite this, many continued to believe Prohibition could work. Drinking and alcoholism had declined across the country; all that was needed to maintain the law was increased federal enforcement, not moderation of or full repeal of the law itself. They also took solace in the fact that no constitutional amendment had ever been repealed.

By the late 1920s, however, the battle for Prohibition’s repeal began. The Association Against the Prohibition Amendment, established even while the 18th Amendment was in the ratification process, helped mobilize growing opposition to the law. One of its members, Pauline Sabin, founded a new women’s group, the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform, in 1929. A prominent Republican who initially supported the 18th Amendment, Sabin increasingly viewed the law as hypocritic and the main reason behind the country’s surge in crime and violence. Her organization challenged the notion that the WCTU represented the sentiments of all American women and reached out to women across the social and economic spectrum, lending respectability to those that supported repeal and out-campaigning the Prohibition advocates.

The same year Sabin founded her organization, the U.S. stock market crashed, triggering a national and global depression. As the 1920s gave way to the 1930s and the Great Depression worsened, many Americans questioned the need to focus on Prohibition’s enforcement while millions lost jobs and stood in bread lines. Politically, the tide began to turn in 1930, when Democrats took back Congress in the midterm elections, arguing that repeal would create jobs and raise revenue for the federal government. In 1932, the Democratic candidate for president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, also publicly announced his support for repeal. Just one month after his inauguration, Congress passed the 21st Amendment, repealing the 18th. It was ratified on Dec. 5, 1933, less than one year after its introduction.

Prohibition’s legacy continues to live on. Dry laws still exist in some states and localities; Mississippi, Kansas and Tennessee are considered dry by default, as counties must authorize the sale of alcohol for it to be legal. The days of the all-male saloon ended with Prohibition, never to return. Today, the nation’s bars and taverns are places where men and women drink and socialize together as they did in the illegal speakeasys of the 1920s and 1930s. Current moderation laws, advocated by some during Prohibition, make consumption of alcohol in America today much less accessible than during Prohibition.