00:00 - 00:29

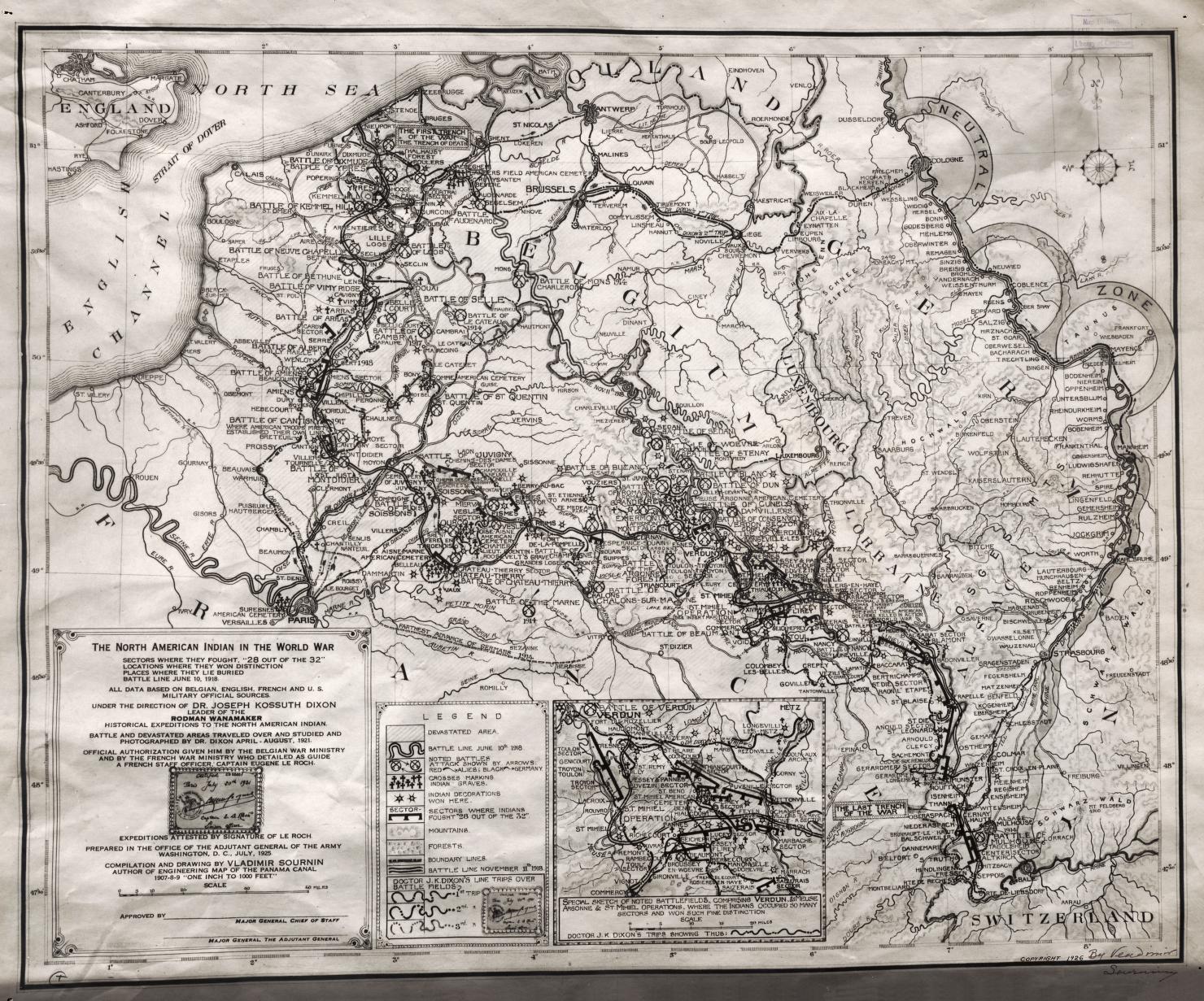

Well, you have, of course, a legacy of not-so-great treatment and the loss of major, you know, most of the continent, etc. But part of the understory that gets lost: there are tribes that had signed particular treaties with the United States, and some also with Canada, up in Canada, where they pledged to voluntarily fight should America be attacked, and the same way, should Canada.

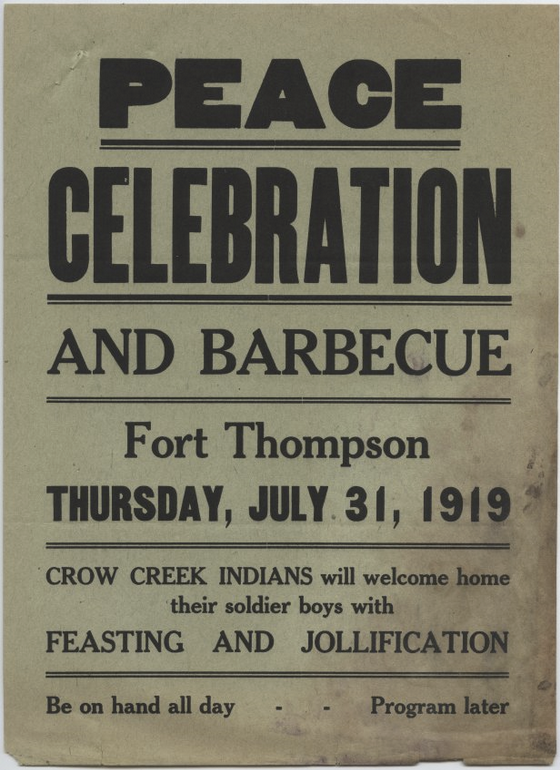

00:29 - 00:50

So you had some groups that felt that they were honor-bound and treaty-bound to support the war cause. And people enlisting because of that, because they wanted to support, in how their tribe had agreed or give their word and everything. You also had people, for example - there are a lot of reasons why natives served in World War I:

00:50 - 01:15

a lot of cultures came from cultural traditions where veterans were extremely upheld in the community. It was seen as the traditional protector. So all your other cultural components were at risk if you could not protect your community and protect your people. And so veterans have always been very, very elevated in most Native American cultures. Another condition was the boarding schools.

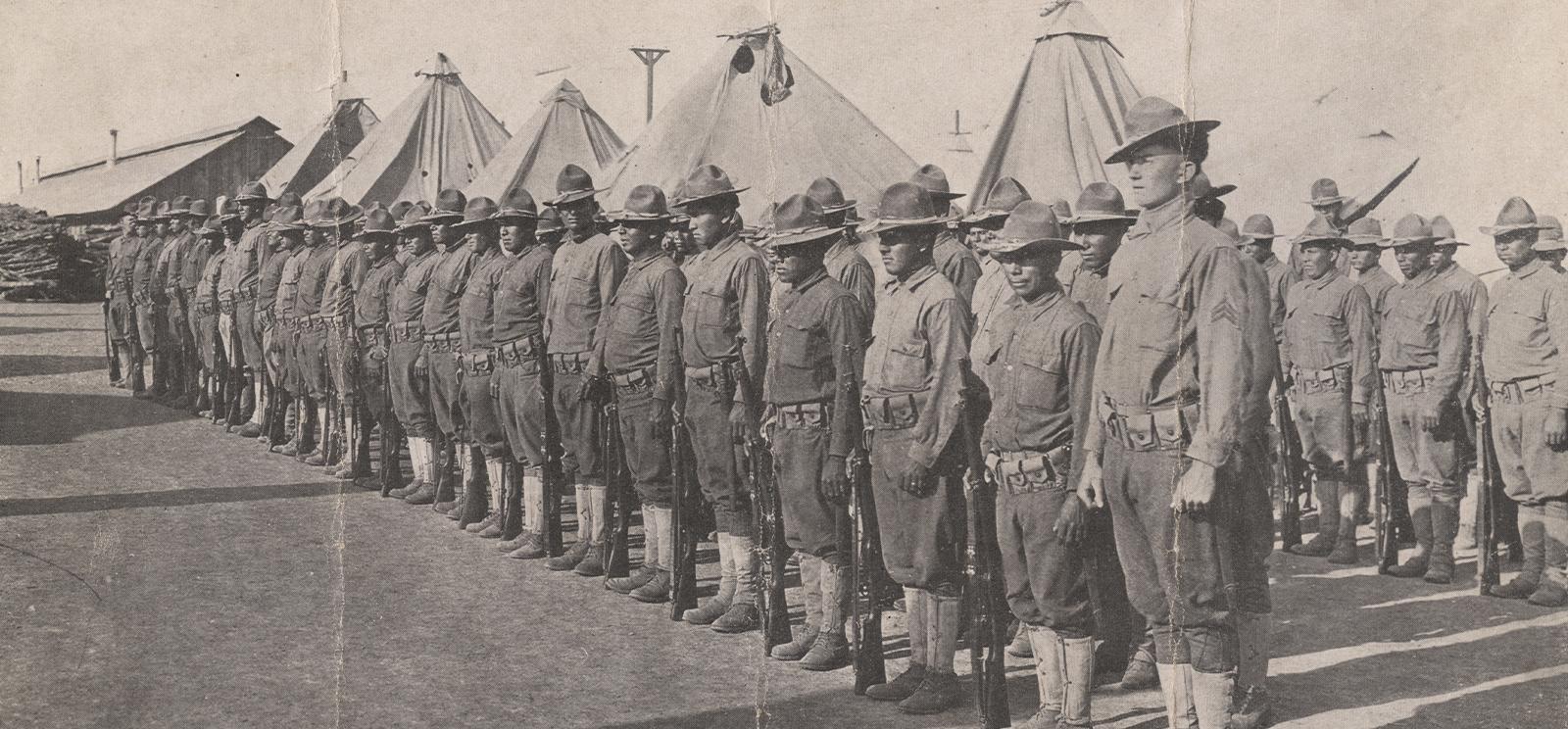

01:15 - 01:43

So the majority of the veterans that ended up in World War I went through Indian boarding schools, whether it be a local school or be an out-of-state boarding school. So they were already preconditioned a lot of ways - in terms of - kind of like a cadet-type school. They had lived in bunks and kind of quarters, wore military style uniforms, marched to class, some short order drill. Some units - like up at Haskell and everything,

01:43 - 02:15

even had kind of like ROTC or military cadet units. So they actually trained in weapons and marching and things. So a lot of them came out of these, a school to where a lot of the things that would be covered in basic training were already familiar to them and everything. If you look at their testimonies at the end of World War I, some men joined out of economic necessity - simply a chance for income and to send that income back home to their families to take care of their families.

02:15 - 02:41

There are some that had joined for the sake of exploration and a chance to travel, because that was a very traditional part of warrior culture in many societies, was to travel to other lands and explore. Some mentioned that they left it to escape the conditions of the reservation, which were very bleak and economically depressed at the time.

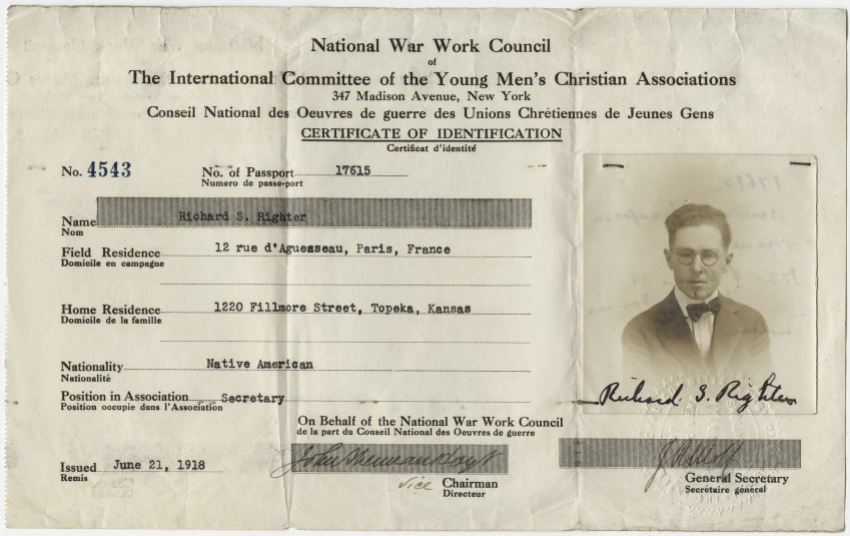

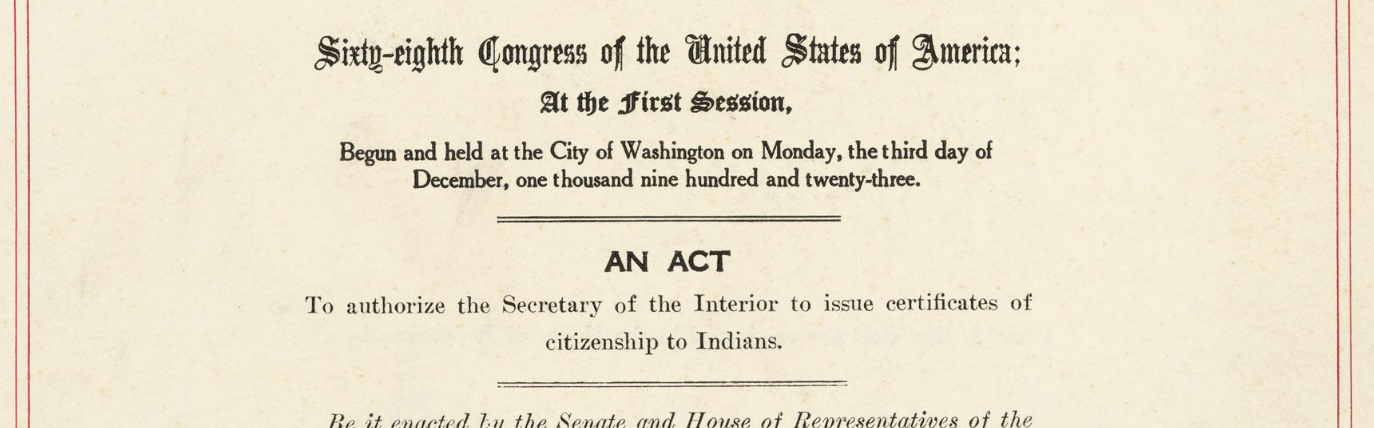

02:41 - 03:15

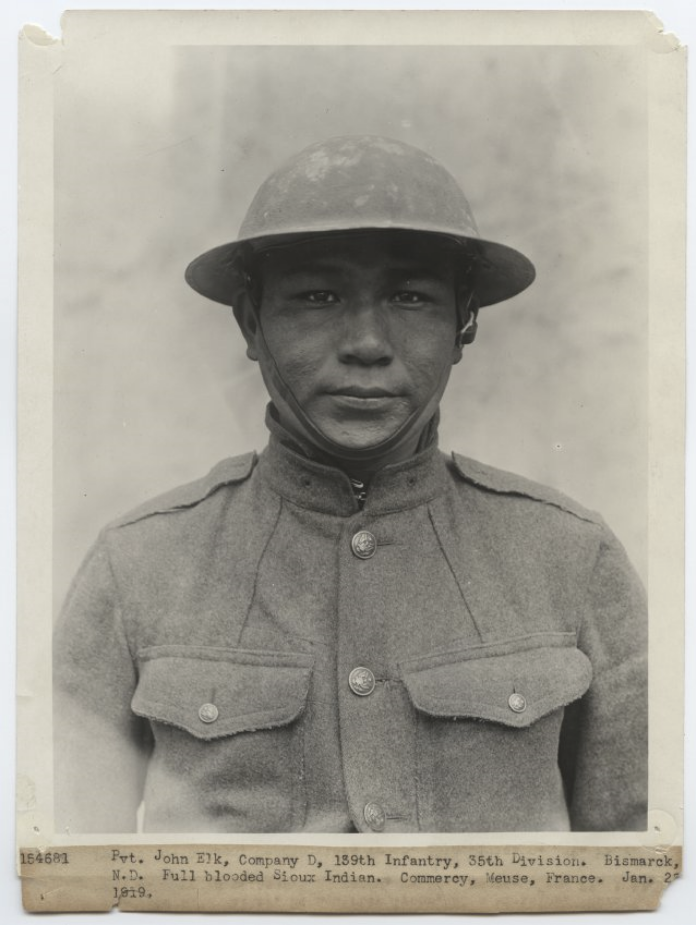

Some people also joined because in their families, they had already established very long traditions of military service - both aboriginally, but even in things like the Revolution, the War of 1812, Civil War, the Spanish-American War, and now World War I. So there are many, many factors there. There are people that also went because they thought it could improve their political and their legal status and gain more rights, more favorable treatment or more acceptance and more rights.

03:15 - 03:40

So it is a very mixed bag of reasons that can vary from one soldier to the other. Another another issue is that some people wanted to show and put behind stereotypes of, you know, not supporting or not being, you know, a part of the nation and things of that nature.

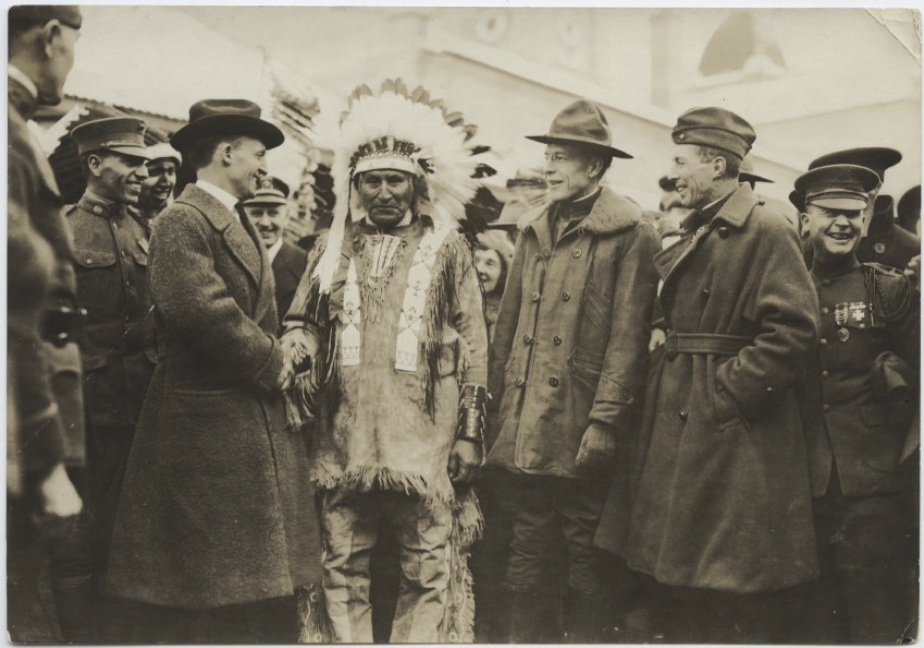

03:40 - 04:05

And so while still trying to carry the traditional culture forward, it was a way to reinforce that or show that we are, in a sense, with you. And then if you look at it from the native standpoint, they still have lands - greatly reduced - they still have lands that technically, legally have never left their hands. So there is still tribally-owned trust status Native American land, and your community and your people.

04:05 - 04:31

So on one level, they are protecting those remaining lands and their respective nation or tribal people. On a second hand now, they're also protecting the United States as a whole and all the other peoples. So I've always looked at it as a kind of a dual duty. It's almost like a dual citizenship or a dual duty, that is qualitatively different than any other American at that time.

04:31 - 04:52

And the willingness to join, you know, coming out of the boarding schools - some of the cultural suppression - the willingness to join and serve, and the willingness to use their language and code talking, and some of these things I've always thought speaks very highly of their - of a level of patriotism and character.