While trenches awash with mud was a devastating factor for millions on the front lines, the warring militaries had another critical condition to consider – the cold. Frigid rain chilled soldiers across Belgium and France. On the Eastern Front, snow and ice significantly hindered troop movements. Operations in Siberia introduced American forces to the brutal realities of sub-zero temperatures and biting wind chills.

Keeping soldiers alive in cold weather required purpose-built garments that could be manufactured quickly and maintained easily in extremely rough conditions. In the final days of the Battle of the Somme in 1916 and into the early months of 1917, an exceptionally brutal winter tested soldiers, pack animals and equipment – sometimes literally freezing trench warfare in place. Fighting in the cold was a war unto itself.

Pre-WWI History

For centuries, European armies waged battles during a traditional warmer “campaign season.” But war was evolving in the decades leading up to WWI. Year-round conflicts meant Western and Eastern European militaries had to expand their requirements and expectations for soldiers’ cold weather gear (though uniform and material shortages persistently threatened the readiness of all combat troops).

During the Franco-Prussian War, French infantry soldiers were issued sheepskin vests and woolen great coats or tunics that could provide some buffer against the cold and potential injury.

It means the government has provided these supplies for a specific purpose.

In the Russo-Japanese War of 1905 to 1906, winter field dress for Russian soldiers included bashlik, a type of hood that would be worn over a lambswool winter cap, and a long woolen great coat with sleeve cuffs that could be turned down to protect a soldier's hands from the cold.

Outfitting WWI Militaries

By 1914, increasingly standardized winter gear for many European militaries meant service members dressed similarly both on and off the battlefield. Like all uniforms, cold weather clothing needed to balance form and function for a variety of conditions.

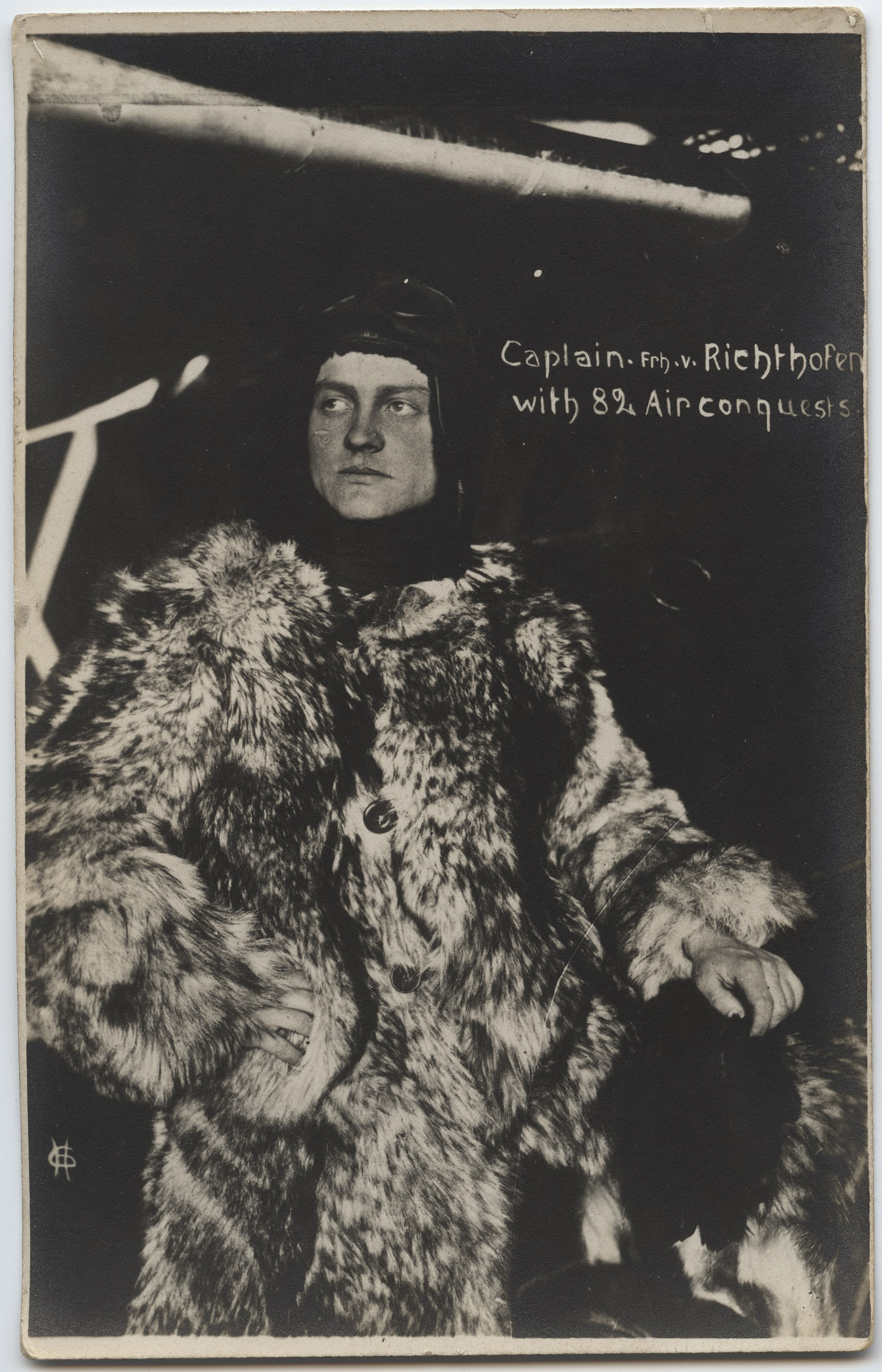

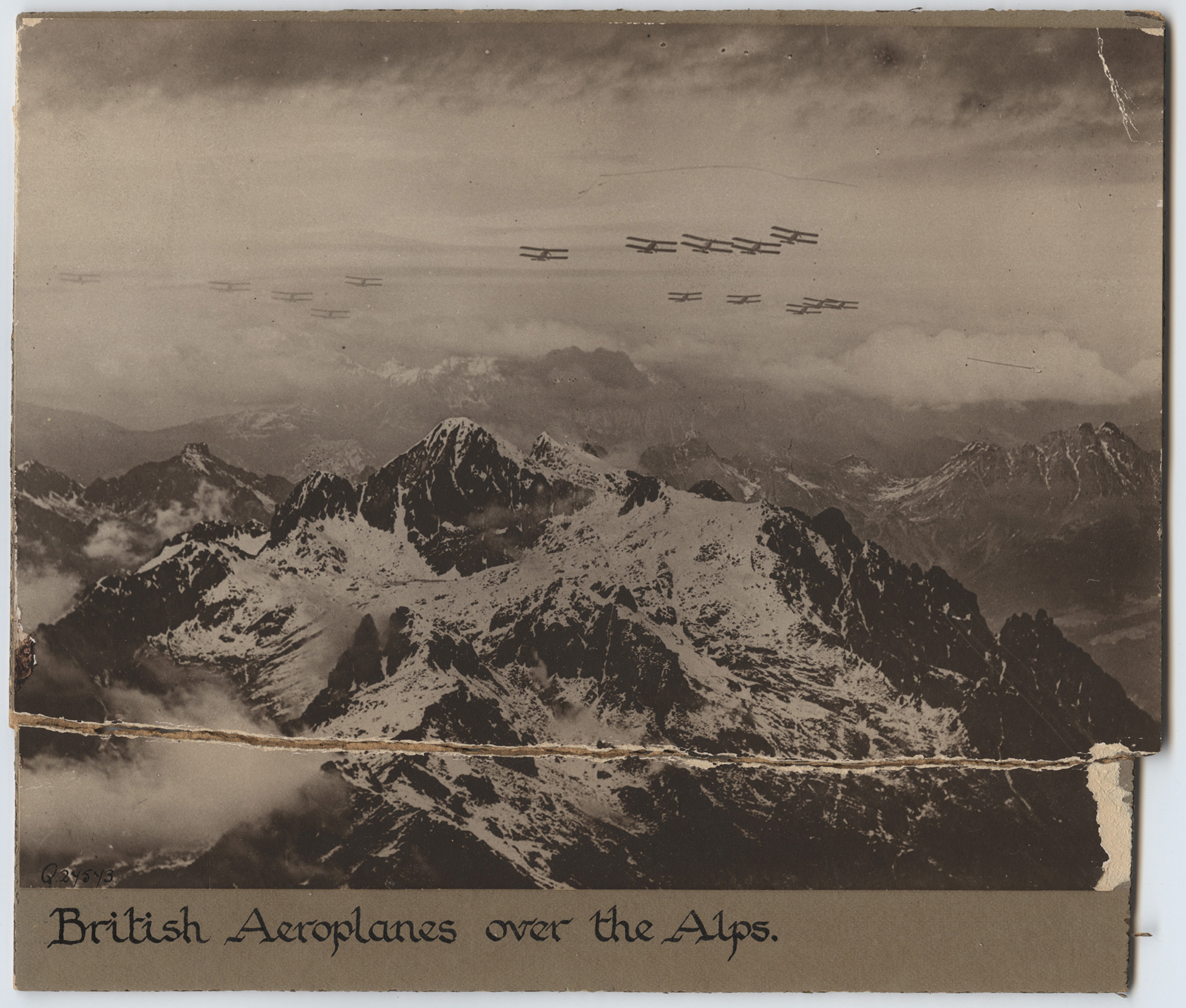

Most soldiers in the German Imperial Army were outfitted with the standard grey wool uniforms, coats and durable leather boots. Soldiers in specialty units would adapt their outfits for environmental conditions as needed. German flying ace Captain Manfred Von Richthofen – nicknamed “the Red Baron” – was known to sport heavy fur coats to ward off the biting cold of an open cockpit in early fighter aircraft.

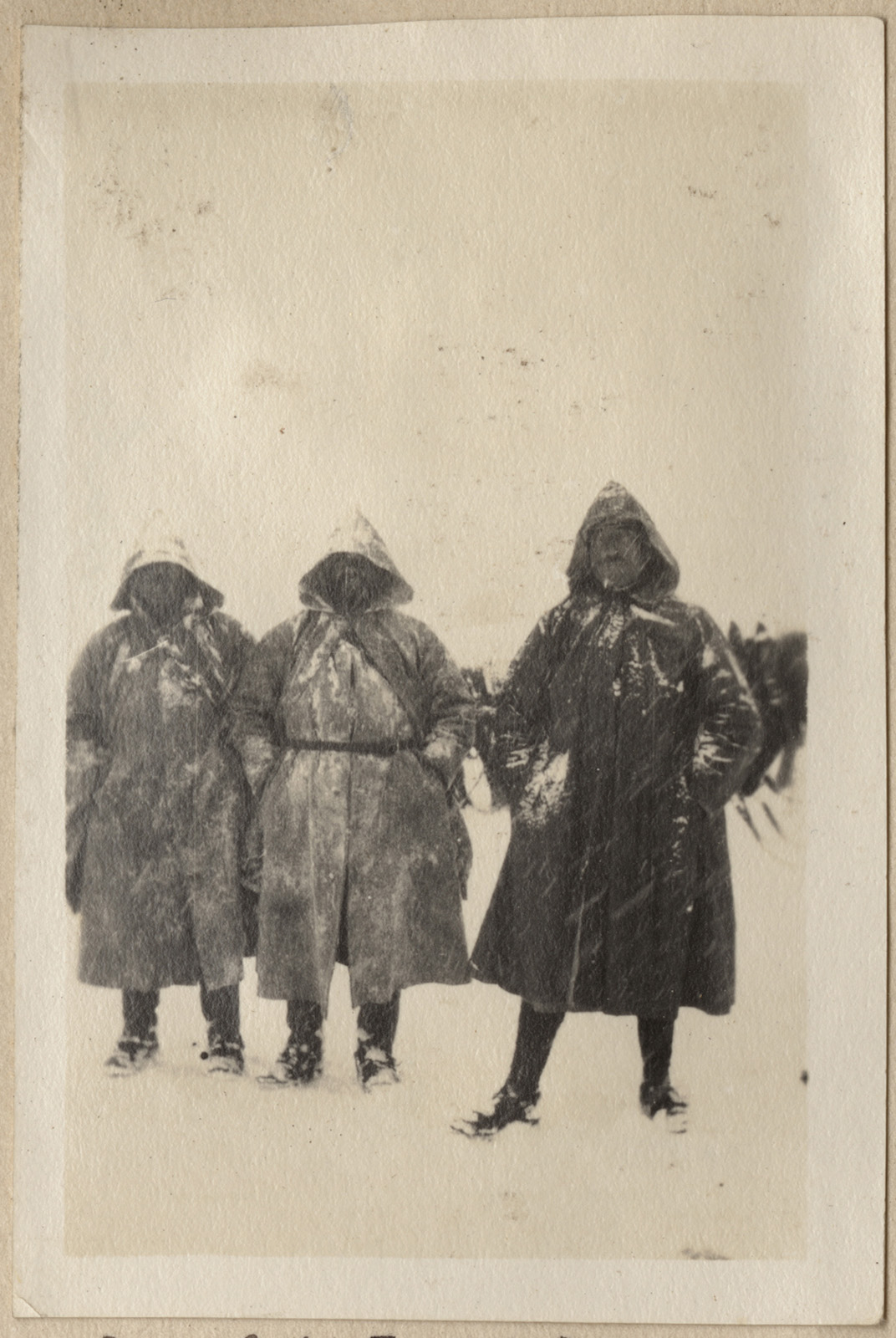

For French, Belgian and British soldiers entrenched along the Western Front, woolen long underwear, sweaters, scarves and puttees provided some defense against cold – until those items became sodden and caked with mud. Some British and Canadian soldiers had access to rain capes (collared ponchos made from canvas duck cloth). These provided some waterproofing and kept the wearer’s clothes and upper body somewhat dry.

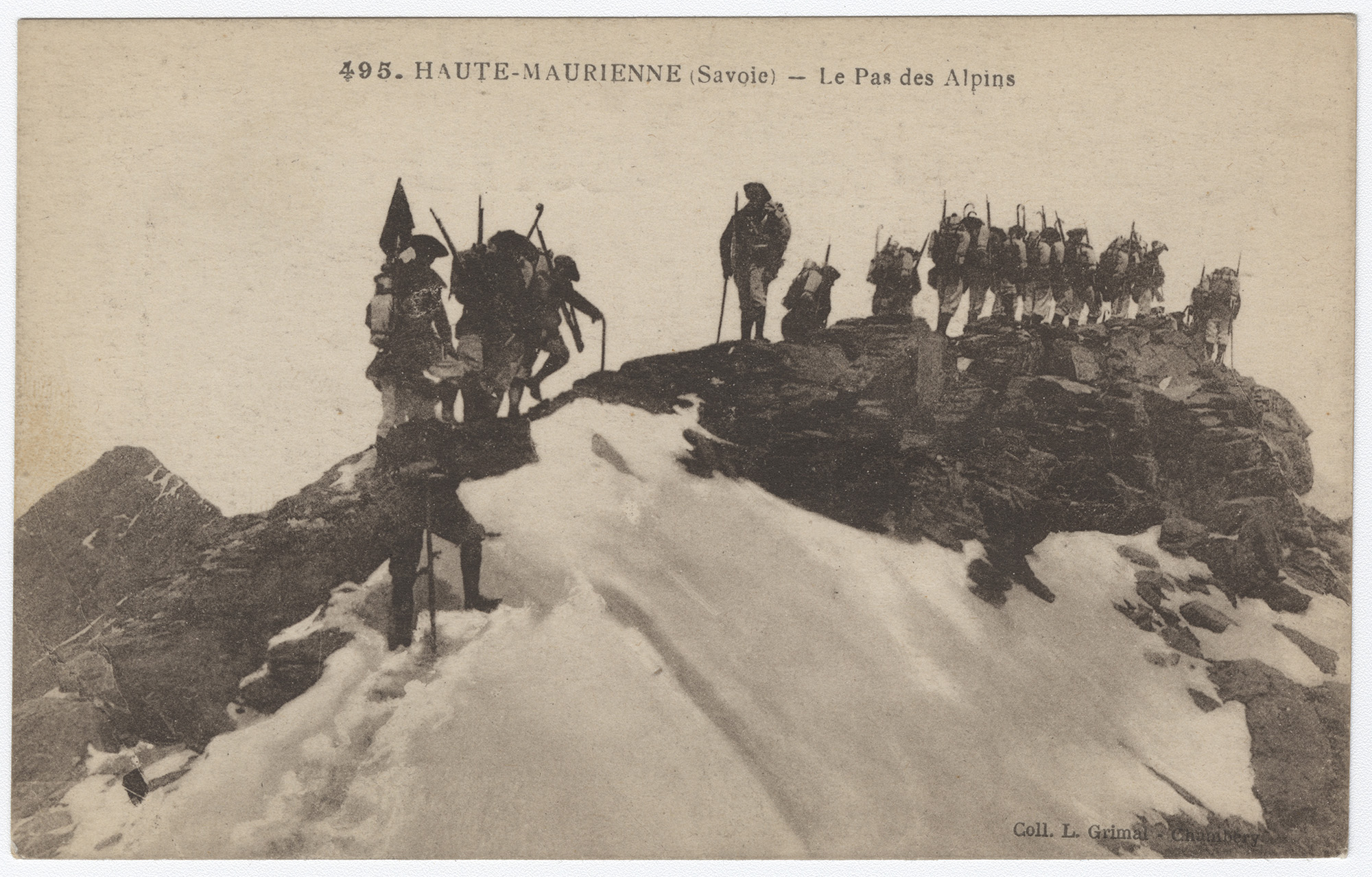

Along more southern front lines in the Alps and the Italian Dolomites, soldiers faced the dual challenge of cold conditions and rugged alpine environments, necessitating a new type of winter gear: mountaineering equipment. Crampons, harness ropes and pick axes accompanied heavier coats and sheepskin lined caps and mitts. The new climbing gear added to the complexity of fighting and resupplying outposts in treacherous mountain environments. The heavier clothing layered under the gear also increased the physical bulk of soldiers as they were navigating and fighting around dangerous cliffside paths, ledges and steep slopes.

Outfitting U.S. Forces

For American forces prior to 1917, cold weather gear varied widely, consisting of both standard-issue and special provisions. The U.S. Army's M1912 and M1917 winter service uniforms were drab wool with a cotton liner. Marines were also equipped with a service uniform that included a liner for their woolen coats. Soldiers received flannel drab olive pullover tops. Wool trousers and spiral woolen puttees protected the lower leg from dirt, mud and debris, replacing the canvas leg gaiters from the Punitive Expedition of 1911 to 1914.

Like their British and Canadian counterparts, American service members received a new pattern of poncho for rain protection. The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) deploying to extremely cold climates in 1917 were also provided heavy wool overcoats, for “necessary outdoor duty when exposure would jeopardize life or limb.”

Other small accessories complemented service members' cold weather collections. Motorcycle couriers and pilots wore chamois face masks, woolen mufflers and goggles to prevent cold exposure injuries to the face.

Oilskin hats and coats were not only provided to sailors, but to soldiers working in coastal defense and mining companies. For Americans stationed in Alaska or serving in Siberia, fur hats and gloves accompanied their issued heavy overcoats.

Legacies

Of all the innovations in cold weather gear to emerge from the First World War, one piece remains fashionable today: the trench coat. British Hampshire shepherds had worn a traditional gabardine (treated) long-cut coat as weatherproof outerwear long before WWI. Inspired, coat makers created a shorter, lighter-weight, waterproof khaki version that wealthy British officers favored during and after the war – launching brands like Burberry to iconic status.

Today, the development of cold weather equipment is driven by a mix of technological innovation from the commercial sector and military research. Service members worldwide are given gear to protect them from exposure to cold temperatures. In the United States, such equipment is crucial to effective training in extreme locales – from the mountainous Colorado and snowy regions of northern New York to the Arctic circle in Alaska. Drastic temperature variations between day and night in military training locations like the Mojave Desert or Dahlonega, Georgia, underscore the importance of cold weather gear even in places not associated with cold weather.

Much like military manuals published in 1917 that helped AEF soldiers understand how to wear their gear to the Army's standard, today's cold weather and mountain doctrine addresses key lessons that were originally learned and tested in the First World War. Cold weather gear is just one more testament to WWI’s lasting influence on both military and civilian life.