“Coffee is served anywhere, anytime,” wrote Ned Henschel in a note to his mother on July 2, 1917.

While there were no coffee shops on every corner in Europe during WWI, American soldiers and sailors could still get that hot cup of coffee. Rationed at 27 pounds of coffee per servicemember per year, according to “America’s Munitions, 1917-1918”, over 75 million pounds of coffee were provided by the U.S. Quartermaster in 1918 alone. (To serve the most flavorful coffee to nearly 3 million American men and women serving overseas, it was decided that the beans should be shipped green and roasted “over there.”)

Collection object:

A tin of dried (soluble – dissolved in hot water) coffee made to be carried in the soldier’s or sailor’s pocket.

So great was the demand that the U.S. Army took over the relatively new soluble coffee industry – today known as instant coffee – producing up to 6,000 pounds (about the weight of an elephant) per day in 1918.

WWI created a generation of American coffee drinkers, ready to order a cup of joe later in life.

“I have gotten to be a regular coffee drinker now. They make such good coffee here too, plenty of sugar and milk with it,” Thomas Shook wrote in a letter home about YMCA canteen coffee, August 7, 1918.

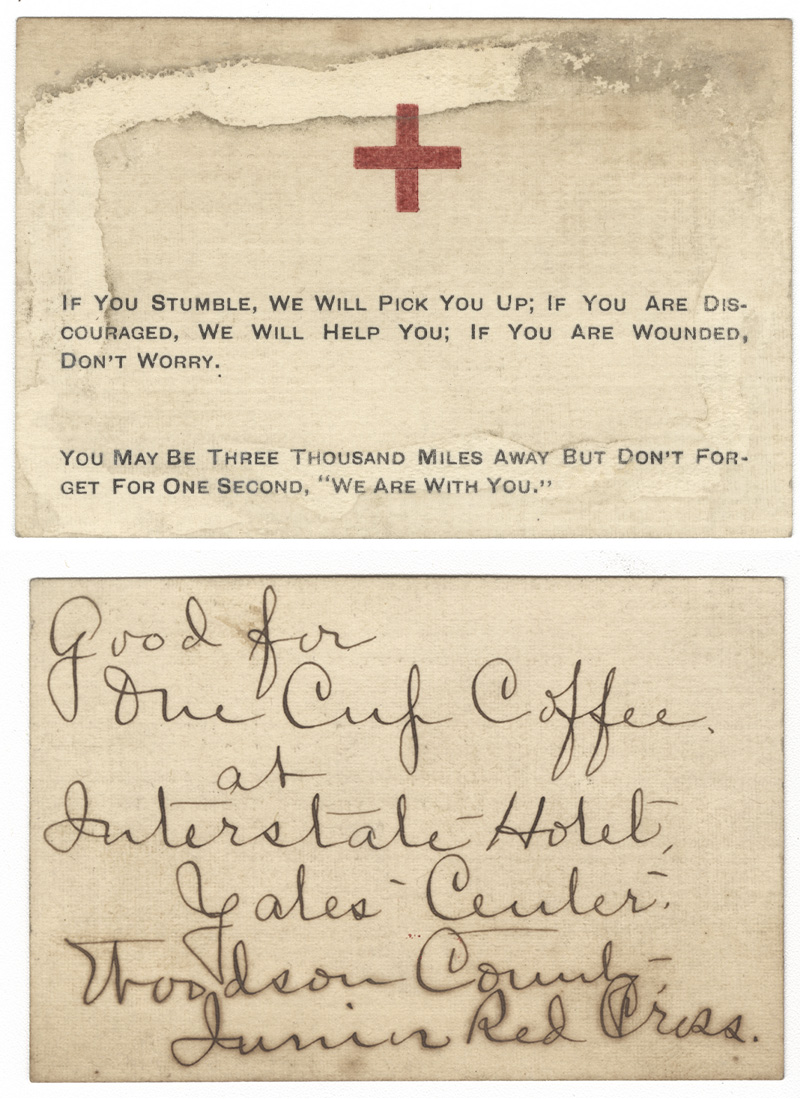

Red Cross card with handwritten note on reverse indicating card good for one cup of coffee

Loose item found in a scrapbook belonging to Walter A. McClain of the 89th Division.

Among the major forces in the war, the German Army rivaled the Americans in their consumption of coffee. In their knapsack, which normally weighed over 21 pounds, the German soldiers each carried the essential coffee tin.

When the British Navy imposed the blockade on Germany, the delivery of coffee to the soldiers and civilians slowly dried up. The government and civic organizations in Germany asserted that substitutes (“ersatz”) like acorns for coffee were just as good (but probably not).

German field tea and coffee strainer