To learn more about the evolution of prosthetic limbs during and after the First World War, visit special exhibition Bespoke Bodies: The Design & Craft of Prosthetics, on display in Wylie Gallery until April 2024.

World War I changed many things, including the approach to healing damaged bodies in the wake of violent conflict. The lessons learned about battlefield amputation and prosthesis use in the years surrounding WWI shaped the way the world approaches artificial limbs today.

While the need and use of artificial limbs goes back centuries, WWI introduced mass production to prosthesis development – unlike anything previously seen in the medical field. Prior to 1900, those who experienced limb differences (whether caused by war or not) could have a limb built specifically for their body. Fittings, therapy and maintenance would often take months, if not years, to refine the limb to the user’s needs and desires. Bodies became bespoke.

By 1900, the advent of mass production and new materials allowed companies to prefabricate components for artificial limbs. Across the globe, from Japan to Germany, prosthetic manufacturers began experimenting with new materials and technologies to blend form and function into standardized limbs. In the United States, patents for various types of prostheses were posted to the U.S. Patent Office throughout the war, with small companies vying for business with international aid organizations. Carnes Arms, E-Z-Fit Liberty Legs, Hangar Artificial Limbs, Rowley legs…the market was vast and fiercely competitive. Many manufacturers sought a coveted partnership with the U.S. War Department and Walter Reed Military Hospital for the ability to mass-produce limbs for returning injured veterans.

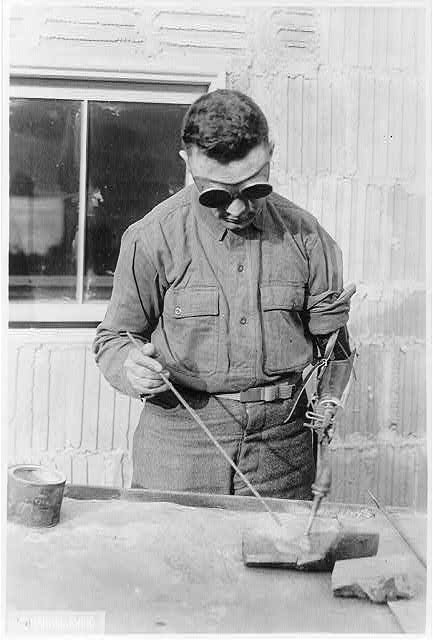

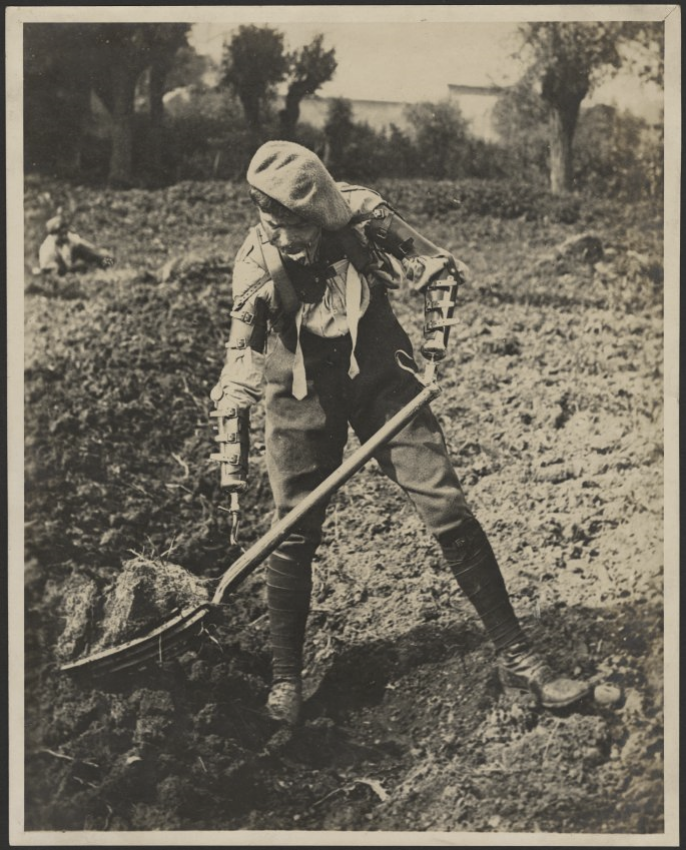

While a missing limb’s form could be replicated, regaining the limb’s function was another matter. Many of the new mass-produced artificial limbs lacked reliability and durability for industrial labor or agricultural work. Other limbs lacked the dexterity and fine motor skills required for crafts work. A vast majority of the one-size-fits-all limbs were uncomfortable or ungainly. The U.S. Government had sought to replace limbs to make people whole again and prevent an over-reliance on charity. Instead, they exposed a difficult friction point between the expectations and realities of rehabilitation. Some soldiers began adapting to their limb loss with unique solutions.

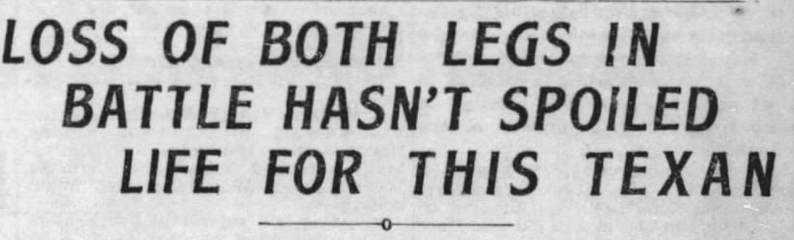

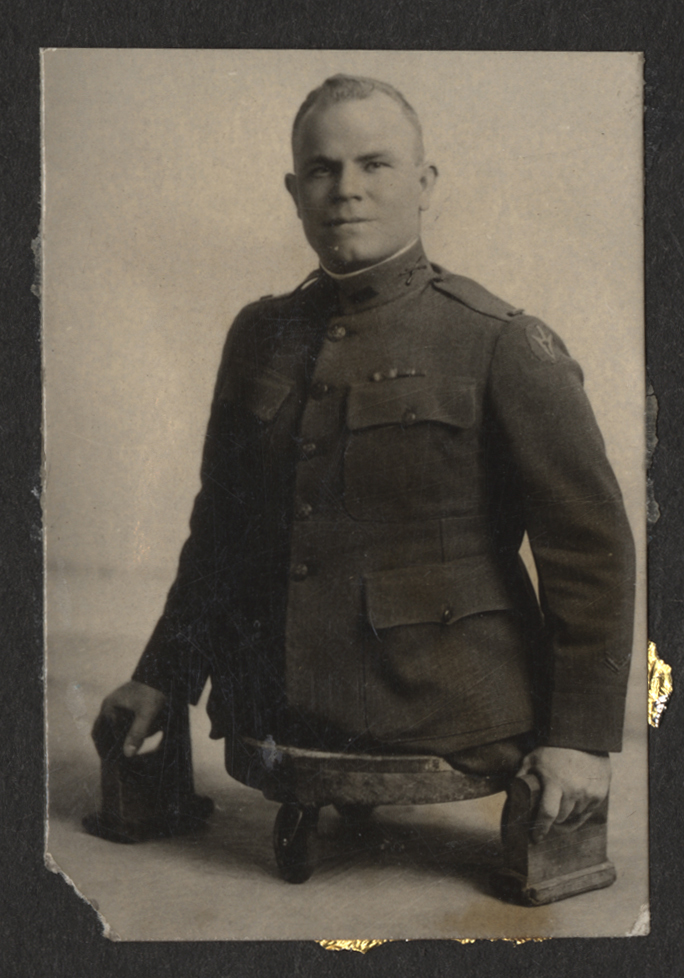

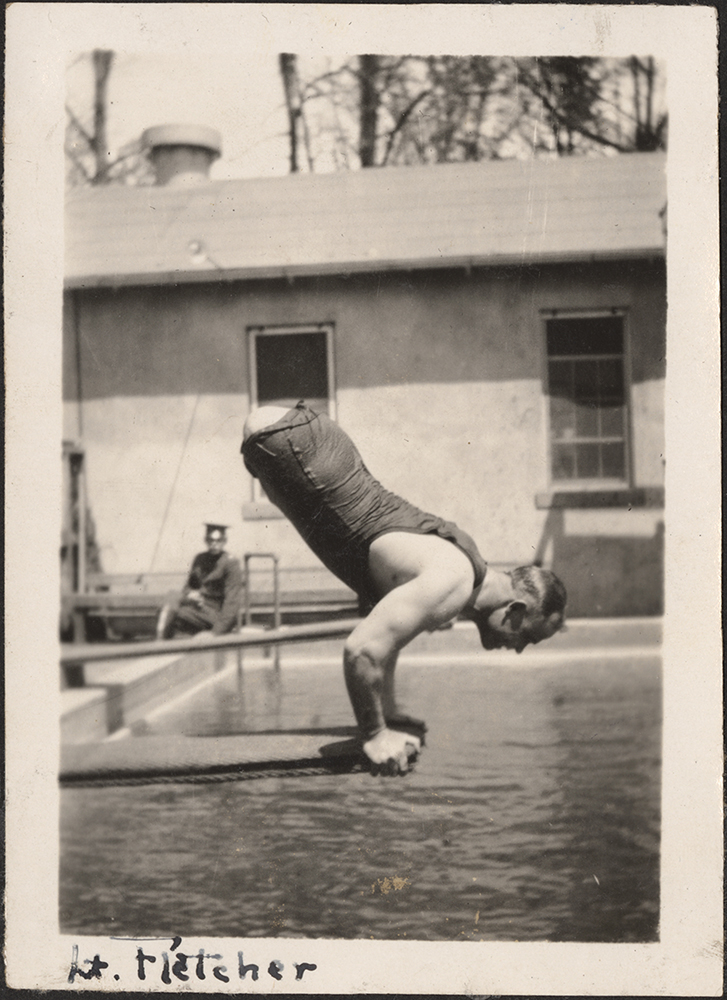

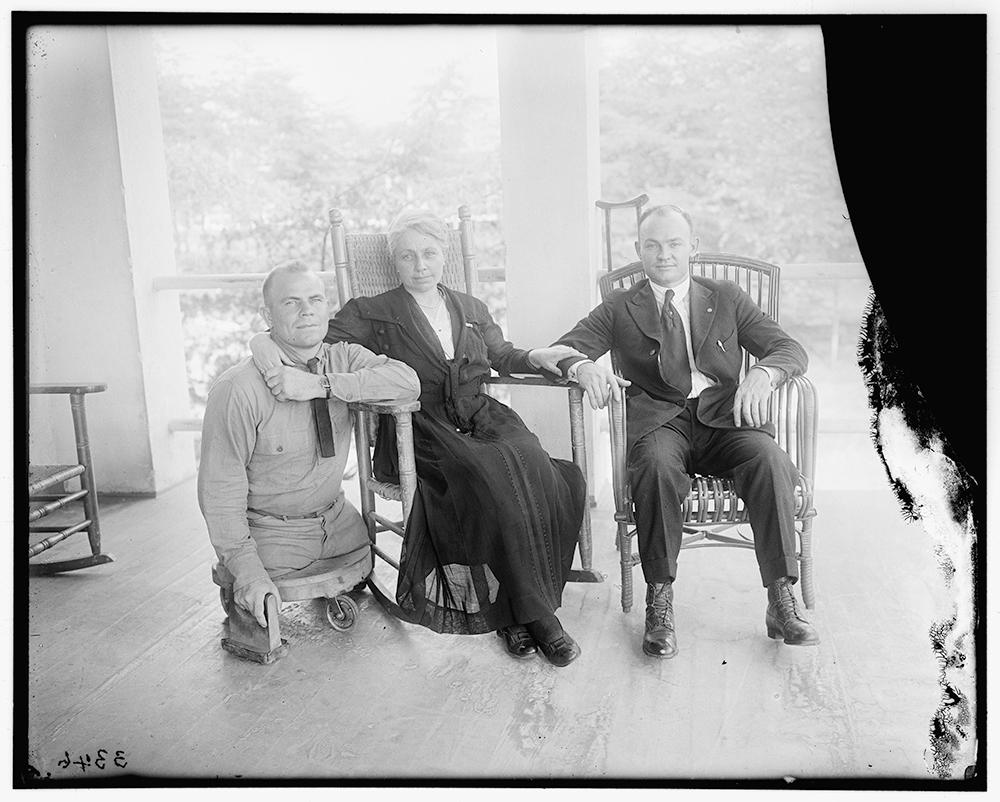

2nd Lieutenant Robert Stell Fletcher, a Texan in the 36th Division, had both legs amputated after suffering shrapnel wounds during in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. With both legs amputated nearly to the hip, doctors had trouble attaching prosthetic legs to his body. Most artificial legs of the time were attached by straps to the thigh. For mobility, Fletcher adapted a roller seat with hand blocks to propel himself.

His persistence caught the attention of many at Walter Reed Hospital. Newspapers across the country wrote stories, gaining him an introduction with President Warren Harding. Eventually, he was able to drive a car, climb ladders and swim without his legs. Following his rehabilitation in Washington D.C., he returned to Texas, married, and had four children before his death in 1947.

Fletcher’s story, like that of many others returning from service with limb loss, is one of adaptation. In the years between WWI and WWII, prosthesis development would evolve with the lessons and experiences of medical professionals and amputees with prosthetic limbs. The Artificial Limb Laboratory at Walter Reed continued experimenting with interchangeable and standardized components to build new limbs, but it also recognized that the one-size-fits-all approach for amputee care needed adaptation as well. New leadership at Walter Reed after WWI adopted a multidisciplinary approach to surgery, therapy and prosthetic construction and refinement. More importantly, they recognized that continuity of care would be a lifelong and personalized necessity for all amputees.

Walter Reed and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs still produce prosthetic limbs for thousands of veterans across the country and around the world. Each limb is built and fitted to the individual: a bespoke lesson from World War I.