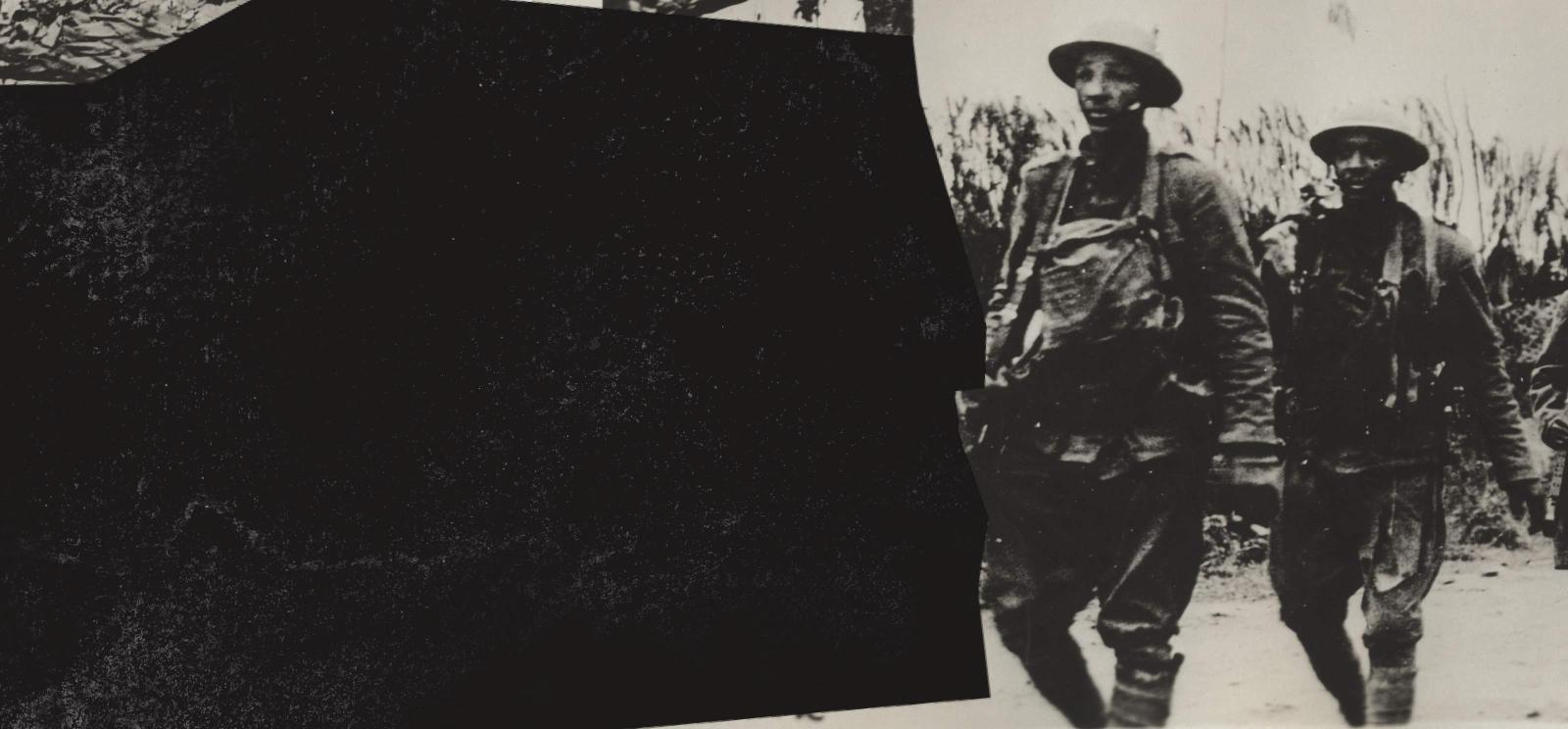

Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow

Explore the struggle for full citizenship and racial equality that unfolded after the Civil War, and leading into WWI, in the newest exhibition at the National WWI Museum and Memorial, Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow.

When slavery ended in 1865, a period of Reconstruction began (1865–1877), leading to achievements like the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution. By 1868, all persons born in the United States were citizens and equal before the law, but efforts to create an interracial democracy were contested from the start. The promise of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments fell short as state laws chipped away at their guarantees and federal court decisions paved the way for a “separate but equal” America, ushering in the age of Jim Crow.

In 1917, the United States declared war on Germany and entered World War I. At the time, African Americans made up only 10 percent of the population, but a total of 13 percent of the segregated United States armed services. Though the American military reflected the diversity of its population, the majority of African American soldiers – nearly 80 percent – were organized into supply, construction or other non-combatant units. However, two predominately African American combat divisions were formed that proved the battlefront capabilities of African American troops. Sgt. Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts, both members of the 93rd Division, 369th Infantry Regiment – later known as the Harlem Hellfighters – were the first American recipients of the French Croix de Guerre for bravery. They were not awarded medals from the United States until after their respective deaths.

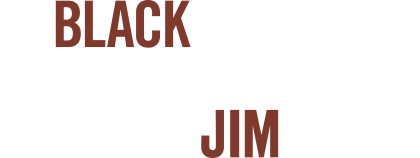

369th Regiment shoulder sleeve insignia (Fighting Rattlesnakes)

National WWI Museum and Memorial

“Black Rattlers” was the nickname given to the 369th Regiment, chosen because of their courage and spirit. In addition to “Black Rattlers,” the 369th Regiment was also referred to as “Men of Bronze” and “Harlem Hellfighters.”

French Croix de Guerre medal

National WWI Museum and Memorial

Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts were the first Americans to receive the French Croix de Guerre medal. The Croix de Guerre was first awarded during WWI and is France’s highest honor for acts of bravery on the battlefield. Both Johnson and Roberts were members of the US Army, 369th Regiment that was first attached to French units in WWI.

Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow follows the end of the Civil War to the end of World War I, highlighting the central role played by African Americans in advocating for their rights. It examines the depth and breadth of opposition to Black advancement, including how Jim Crow permeated the North. Through art, artifacts, photographs and media, the exhibition highlights these transformative decades in American history and their continued relevance today.

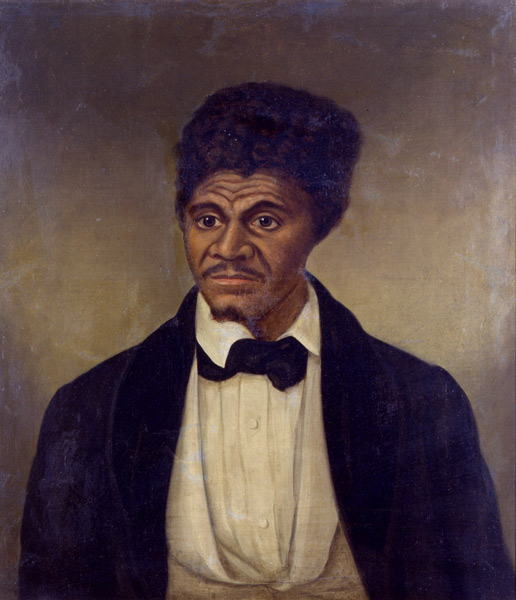

Dred Scott, after 1857

Unidentified artist

Oil on canvas

New-York Historical Society

Dred Scott was a Missouri slave who sued for his freedom. He argued that he had lived with his master in the state of Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, places where slavery was outlawed. Other slaves had been emancipated on these grounds. But in 1857 the U.S. Supreme Court decided against him. It said he had no right to sue because he was not a U.S. citizen. The justices ruled that no black person, free or enslaved, could ever be a U.S. citizen.

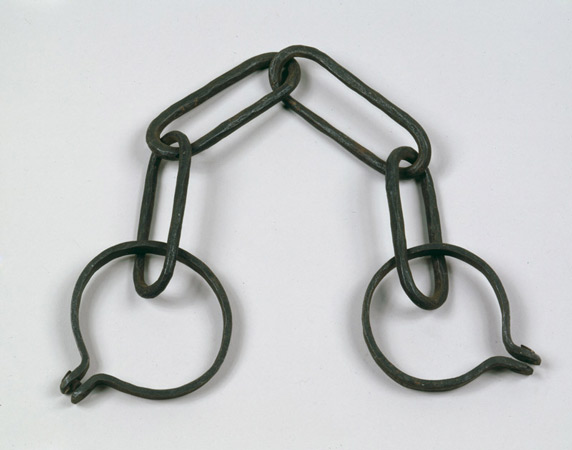

Slave shackles, 1866

New-York Historical Society, Gift of Mrs. Carroll Beckwith

These shackles were cut from the ankles of 17-year-old Mary Horn in 1866. The Thirteenth Amendment had declared the end of slavery a year before. But Mary’s owner still held her captive as a slave and restrained her when she tried to run away to meet her fiancé George. George asked for help from a Union soldier serving as provost marshal. The marshal summoned Mary, removed the chains, and married the two.

Uncle Ned’s School, 1866

John Rogers

Bronze

New-York Historical Society, Gift of Mr. Samuel V. Hoffman

Popular sculptor John Rogers depicted one of the many improvised classrooms African Americans created during Reconstruction. Plaster casts of an original bronze sculpture were sold widely, bringing this sympathetic depiction of black life to a large audience. In this scene, “Uncle Ned” pauses in his work to assist one of his students with a question from her book. A mischievous young boy sits at his feet trying to distract them. In a popular song from the 1840s, “Uncle Ned” is a blind and docile slave. Here, a free “Uncle Ned” is teaching a child how to read—an act that had been a crime in some Southern states during slavery.

Ballot box, ca. 1857

Samuel C. Jollie (active 1857)

Glass, iron

New-York Historical Society, Gift of George H. Dean

African Americans embraced their newly acquired citizenship and took seriously their long-denied rights and responsibilities. Black men voted in large numbers and ran for office. Men and women joined patriotic clubs and local branches of the Republican Party. Black participation in local elections and state constitutional conventions created the first interracial governments in the United States. This demonstration of black citizenship aroused deep hostility among those who had only a few years earlier held African Americans as slaves.

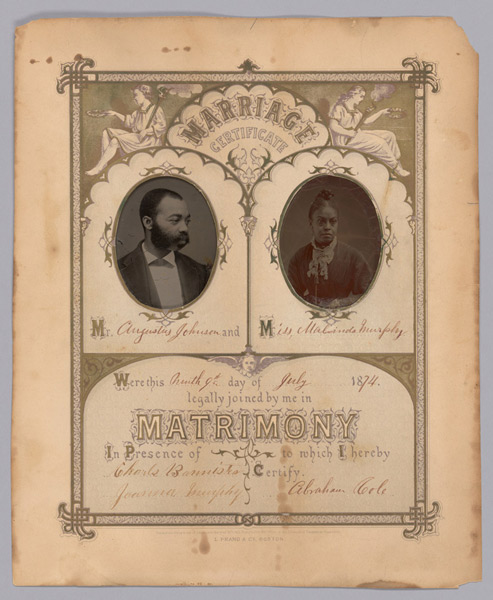

Marriage certificate, 1874

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Louis Moran and Douglas Van Dine

Augustus Johnson and Malinda Murphy married on July 9, 1874, in Spencerport, New York. Many African Americans seized the simple freedom to make long-standing relationships legal. Under slavery, formal marriages of slaves had not been recognized.

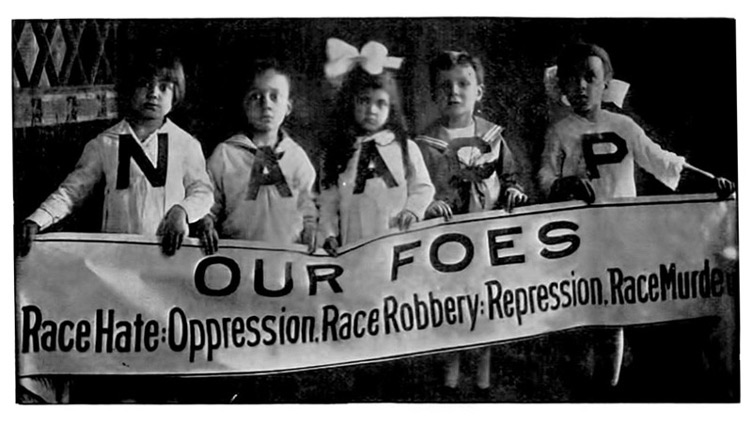

Photograph of young girls from 'The Crisis,' May 1918

Indiana University Libraries

W.E.B. Du Bois and an interracial group of men and women founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) after an assault by whites on the black community in Springfield, Illinois, in 1908. The violence in Abraham Lincoln’s home town convinced many that Jim Crow was not simply a Southern problem. Du Bois launched and edited the organization’s magazine. He titled it The Crisis because he believed America was at a critical moment in its history. The magazine informed a national audience about important issues, built support for the NAACP’s mass protests and legal campaigns, and published the work of black writers and poets.

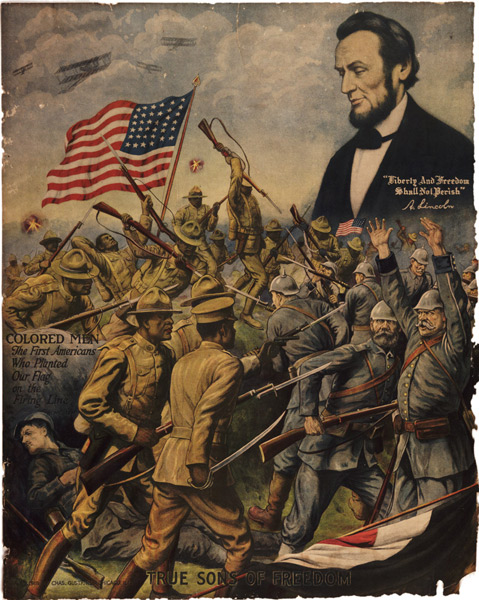

True Sons of Freedom, 1918

Charles Gustrine

The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC09121

Close to 400,000 black Americans served during World War I, but most had been drafted. Moreover, few African Americans saw combat because white military officers believed blacks were better suited to manual labor duties. The example set by the Harlem Hellfighters—which spent more time in continuous combat than any other American unit—directly challenged those prejudices.

The exhibition, on loan from the New-York Historical Society, is curated by Dr. Marci Reaven, New-York Historical’s vice president of history exhibitions, and Lily Wong, associate curator. It was developed in collaboration with New-York Historical Trustee Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr, and Reconstruction-era scholars Dr. Eric Foner, Dr. Michele Mitchell, and other distinguished historians.

Explore More Resources

How WWI Changed America: African American Experience

Black communities in the United States met a war meant to “make the world safe for democracy” with varied perspectives. Learn more with this video, part of our How WWI Changed America project.

Make Way for Democracy! A Google Arts & Culture Story

In an era of federal segregation, the national call as “champions of the rights of mankind” rang hollow. Many African Americans saw the war as an opportunity to redefine their U.S. citizenship and improve social, political and economic conditions.

Red Summer: The Race Riots of 1919

American servicemen returned from the First World War only to find a new type of violent conflict waiting for them at home. An outbreak of racial violence known as the “Red Summer” occurred in 1919, an event that affected at least 26 cities across the United States.

Oral Histories: WWI Soldiers, in Their Own Words

These interviews, recorded between 1978 and 1980, allowed surviving veterans of the First World War to share their experiences, in their own words. The collection includes several Black veterans.

Presenting Sponsor

Honorary Chair

Karen Daniel

Honorary Committee

Debby and Gary Ballard

Kevin Barth

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas City

Alvin Brooks

Ramin Cherafat

Mark Garrett

Hallmark Cards

Andrea and Terrence Hendricks

JE Dunn Construction

Mary Jane Judy

Christine and Sandy Kemper

Sandra and Willie Lawrence

Mayor Quinton Lucas

Leo Morton

Roshann Parris and Jeff Dobbs

Nicole Price

Grover Simpson

Carolyn Watley

Maurice Watson

Lead support for the exhibition provided by National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the human endeavor. Major support provided by the Ford Foundation and Crystal McCrary and Raymond J. McGuire.

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in these programs do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.