Captured

Nearly 9 million.

During four brutal years of the Great War, nearly 9 million people were held as prisoners of war at some point during the conflict. From the shores of Southeast Asia and the Siberian tundra, to mere miles from the Western Front, they were imprisoned the world over – by both sides. Seldom told, their experiences are some of the most common during the Great War.

Captured delves into the stories of life behind the wire: relationships among the prisoners and between the prisoners and their captors, a complex and unique dynamic of mundane daily life and the arduous conditions of captivity. Bound together by suffering and uncertainty, many prisoners and guards were encountering people of different races, religions, languages and cultures for the first time. This exhibition explores how their relationships sustained hope – on both sides of the barbed wire – amid bleak and uncertain circumstances.

“Captured But Not Conquered”

On Nov. 2, 1917, German forces launched a successful raid on their inexperienced American counterparts in the trenches near Nancy, France, killing three and capturing 11 soldiers from the 16th Infantry Regiment – the first U.S. casualties of WWI. German propagandists sought to use the moment to their advantage, taking and distributing photographs of the prisoners in an effort to demoralize the U.S. troops quickly amassing in Europe. It did not go as planned: among the photographs was one depicting a Sgt. Edgar Halyburton, gazing defiantly at the camera with a hand in his pocket and the other clenched in a fist at his side. Within days, the Allies had broadcasted the image internationally for their own propaganda campaigns, where it caught the attention of American sculptor Cyrus Dallin.

First worked in plaster and then cast in bronze, this statue is one of five originals created by Dallin, and the one that Dallin gave to the Halyburton family.

Their historical and personal accounts carry a modern and global impact still seen a century later. Images of WWI prisoners, gazing at cameras across the globe, document a historical juncture in which long-term mass incarceration was becoming a key outcome of fighting. Prominent international military and diplomatic leaders agreed to the humane treatment of prisoners, while evolutions in industry and technology changed the scale and duration of captivity.

Poster Gala de Musique Roumaine

French poster promoting a musical gala to benefit Romanian prisoners of war.

“The soldier may picture to himself the discomforts of trench life, the possibility of being wounded, of loss of limb or eyesight; he may have discounted the possibility of death in battle; but strangely enough, one rarely comes across in the prison camps a prisoner who had ever considered the possibility of being taken captive.”

—Daniel J. McCarthy, The Prisoner of War in Germany, 1917

Soldiers and civilians were never trained in how to be a good prisoner. And as such, no two stories are the same. Yet they each share in the universal longing for freedom, peace and a return to better times.

Walnut Shell Dioramas

Two handmade dioramas in walnut shells made in a German prisoner-of-war camp by Sidney Christopher Hugh Milgate, 1st Royal Naval Brigade, D Company, Collingwood Battalion. One shows a sailing vessel and the other a lighthouse coastal scene.

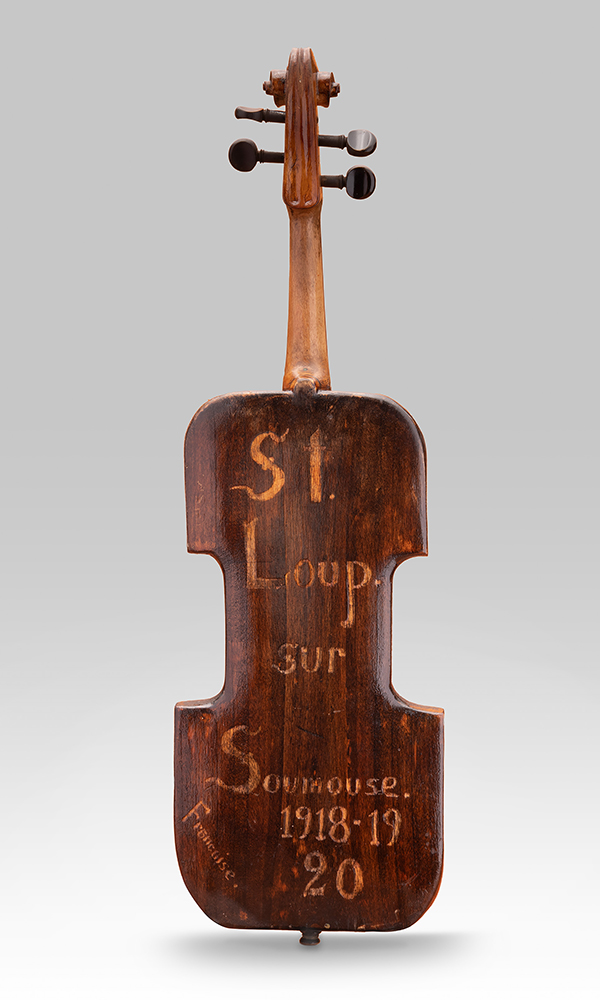

Violin

Handmade violin by German soldier August Christian Voigt while he was a prisoner of war of the French. The violin and case are made of scrap supplies provided by his guards. The top of the violin is marked P. G. 46 [Prisonnier de Guerre number 46]. The back is marked “St. Loup Soumouse, 1918-19-20 Francoise”, indicating where he was held [the prison camp was also sometimes spelled 'Semouse'].

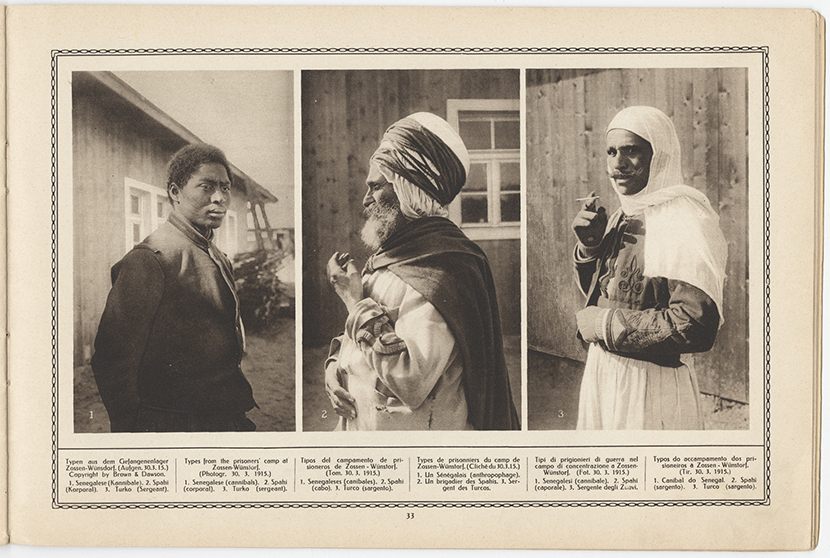

French colonial soldiers held in the Zossen-Wünsdorf POW camp in Germany

Der Grosse Krieg in Bildern, no. 4 1915, Page 33

Entry in the Online Collections Database

Learn more about the camp these soldiers were held in – built specially for Muslim POWs – in the online exhibition Fighting with Faith: A WWI POW Camp of Propaganda.

Russian POW Coat

Russian coat (mendir) worn by a Russian officer in a German or Austrian prisoner-of-war camp. Made of brown fabric with wooden buttons, the white square above the left pocket is marked “R26 – VII,” which could have been the number for the prison camp. The orange cloth collar tabs are also marked R26 [possibly his prisoner number]. The wide orange armband sewn onto the left sleeve also identified the wearer as a POW.

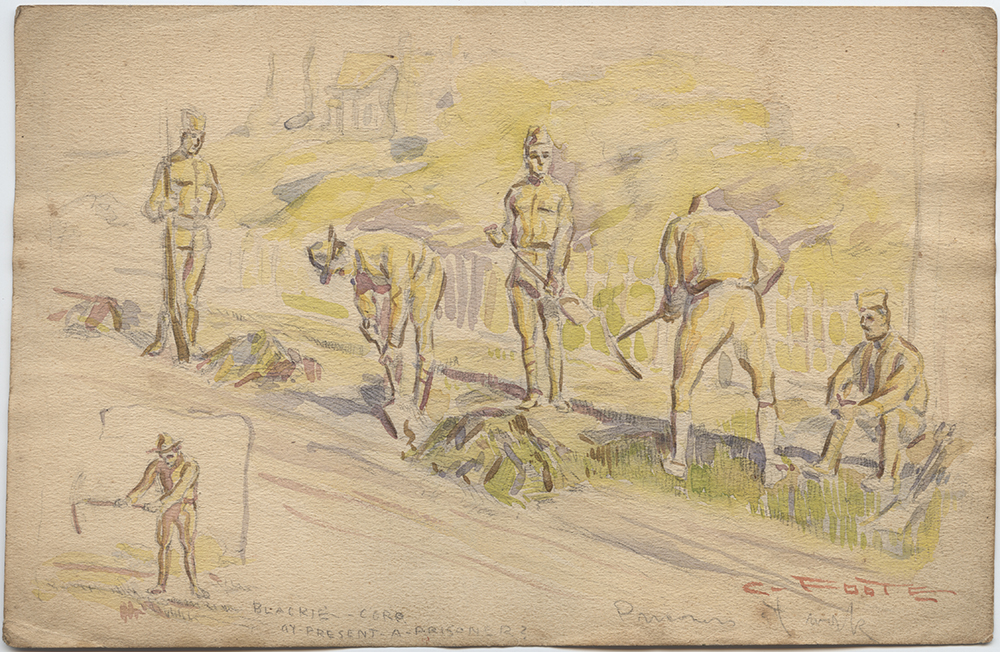

"Prisoners at Work"

Watercolor by Curtiney George Foote of American POWs cleaning a street.

Alphabet Soup Plate

Civilian child's enameled metal plate with an alphabet and clock design. Probably used by prisoners of war for mess in a POW camp in Germany.

Russian Wooden Box

The lid of this wooden box is carved with the dates 1914-15-16 and [translated] “Memory of POW” or “Remember POW.”

Edens Portrait

Oil portrait painting of 1st Lieutenant Louis M. Edens in full uniform. The painting was done by a Russian prisoner of war (name unknown) while Edens was a POW in the German camp in Villengens, Baden, Germany.

Explore More Resources

Collections Spotlight: Bulgarian Prisoner of War Camp Scrapbook

Spotlight on a scrapbook that helps to tell the story of the Bulgarian prisoner of war camp in Central Bulgaria at Philippopolis, Plovdiv, that held approximately 5,000 Allied prisoners.

Collections Spotlight: Ottoman Empire Souvenir Snake

Spotlight on a crocheted beaded snake made by Turkish POWs.

The Escape Artists - Neal Bascomb

In the winter trenches and flak-filled skies of World War I, soldiers and pilots might avoid death only to find themselves imprisoned in POW camps. Join New York Times best-selling author, Neal Bascomb, as he discusses his highly-anticipated book, "The Escape Artists: A Band of Daredevil Pilots and the Greatest Prison Break of the Great War". Using rarely seen memoirs and letters, Bascomb recounts the spellbinding story of the downed Allied airmen who masterminded the remarkably courageous—and ingenious—breakout from Holzminden, Germany’s most infamous POW camp.

The Confidence Men - Margalit Fox

Two British officers have been taken prisoner and are being held in Turkey. Harry Jones, a lawyer, and Cedric Hill, a magician must use their instinct to bamboozle their iron-fisted captors. With nothing but a handmade Ouija board to keep the prisoners entertained, a Turkish officer approaches the men to ask if they could help him find a buried treasure. In a story that is almost too good to be true, author Margalit Fox explores Jones and Hill’s escape from captivity and their journey to freedom in her new book "The Confidence Men".

Sponsored By