Rearranging History: Daniel MacMorris and the Panthéon de la Guerre

At 402 feet in circumference and 45 feet in height, the Panthéon de la Guerre was not only the most ambitious artistic undertaking during World War I, but upon completion in 1918, it was considered the largest painting in the world.

Forgotten after exhibitions in Europe and the United States, when artist Daniel MacMorris (1893-1981) learned from a 1953 Life magazine article that the Panthéon was in the U. S., he saw a golden opportunity. MacMorris, who was in charge of decorating the Liberty Memorial, knew the panorama intimately. He had seen it in Paris as a doughboy and had studied it closely in the 1920s as a student of the Panthéon artist Auguste Gorguet. MacMorris thought the Panthéon would be perfect for the one remaining wall in Memory Hall without a mural.

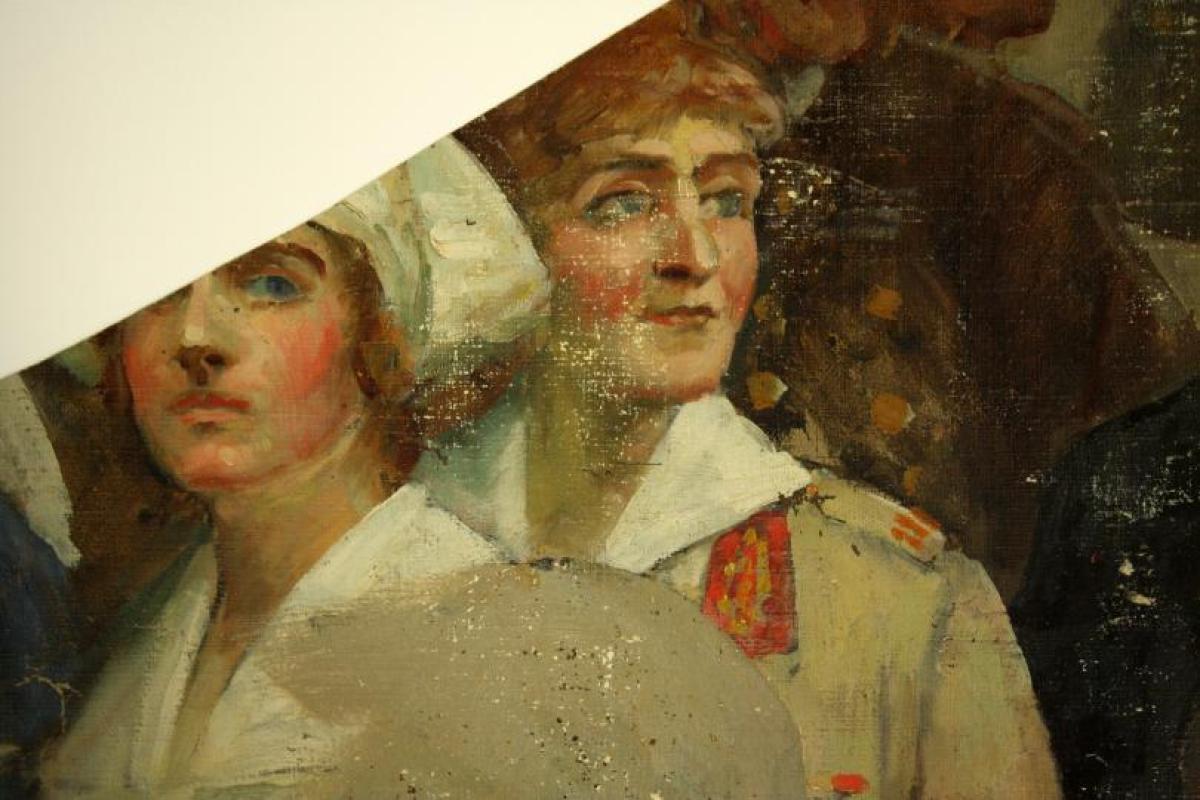

After acquiring the painting, MacMorris photographed it in detail. He cut out the figures in the photos and used these like movable puzzle pieces to work out how best to reduce and reconfigure the composition – an effort he compared to “whittling down a novel to Reader’s Digest condensation.” After deciding whom to include and where to place them, he took scissors to the canvas. He cut out selected figures, flags, and other passages and added these to either side of the original American section.

MacMorris repainted many figures and other elements for reasons of scale or composition, and he painted over the many seams to make the painting look like a single, unified work. He added four people to the American section (by painting their faces over existing figures): Harry Truman, Franklin Roosevelt, Bernard Baruch, and Colonel Edwin House (who had been painted out of the panorama in 1927). At the far left side he painted in the two principal artists of the original composition. Finally, MacMorris invented a Woodrow Wilson-like quotation – he could not find a Wilson quote that he thought was appropriate and would fit – and placed it across the top of the painting. After more than two years of work, the newly reconfigured, American-focused Panthéon was dedicated on Nov. 11, 1959.

What happened to the unused portions of the original? By far most of what MacMorris did not use he threw away. He sent several larger, excised passages back to William Haussner, the Baltimore restaurateur and art collector who donated the Panthéon to the Liberty Memorial. Haussner displayed many of these in his eponymous restaurant until it closed in 1999, after which they were sold at auction. MacMorris doled out other pieces to the art students who helped him reconfigure the painting. Still others he gave to influential Kansas Citians, some of whom have since donated the fragments back to the Museum.

MacMorris did keep several small fragments in the National WWI Museum and Memorial’s archives, many of which have not been seen in public since the Panthéon was last exhibited in its entirety in 1940 and are showcased in the exhibition.